NON-Academic writing

August 2022

June 2022

The Past as Present: Soylent Green today

Film Quarterly Quorum (online only), published 24 June 2022

(Read "author's cut" of this article on the Blog page)

May 2021

November 2018

IN FOCUS: ME (Special section of IDFA 2018, programmed by Laura van Halselma and Alisa Lebow)

A program all about “Me” suggests a few things, some of which turn out to be correct, others mistaken. This amazing program features films from the 1970s to today, ranging in approach and technique from the epistolary avant-garde of Chantal Akerman’s News from Home to the clay figurines of Rithy Pahn’s The Missing Picture. It’s an investigation into the personal filmmaking that has been transforming documentary for decades. The films all foreground the experience of the filmmaker in some way and emphasize the subjective point of view. But miraculously, these films aren’t just self-absorbed exercises in navel-gazing, as the title might also suggest. More than the first-person singular perspective that “me” implies, the personal and avowedly subjective use of this medium is actually much more about the first-person plural, making it a cinema of “we.” To focus on oneself in a film is no more an act of self-indulgence than it is in the writing of a memoir or diary, or a poem for that matter.

...

And yet, why shy away from the personal here? Why insist that these films have to be engaged in looking outwards towards representing “others,” to the extent that many other documentaries are? What if we were to also find room in the vast arena of documentary practice for those films that interrogate personal problems, family dynamics, relationship issues, the loss of a beloved dog? Why not make space for those films that contravene the invisible boundaries of the private, revealing the foibles, the vulnerabilities and the emotional complexities so often obscured in more polite, more distant approaches to representation? Indeed, why always maintain a distance, or perhaps more to the point, why should we be allowed to point a camera into other people’s lives and not interrogate our own? It’s the very act of self-representation and the representation of those close to us where we begin to understand the limits of the private, the bounds of the sayable, the expressive borders that circumscribe our lives.

When a filmmaker makes a film to work through his unresolved relationship with his ex-girlfriend, or her complicated yet loving relationship with her adoptive parent, or even his right to complain of a headache, aren’t they using the medium as much as a psychoanalytic device as a technological one? Isn’t there something truly interesting and revelatory about this fact? Film scholars have long been fond of engaging psychoanalysis in the service of interpreting fiction films, but this opens up a whole other dimension where the filmmaking itself is subject to analysis, as it were. While practicing without a license may be unwise, it’s still interesting to think about film as a type of psychoanalytic space—a prosthetic device that may help a filmmaker work through their deepest traumas or their most pressing conflicts. One of the early dreams of cinema was that it could become as expressive a medium as pen and paper, or paintbrush and canvas, as immediate, as reflective, as personal. Every single film included in this section is testament to the fact that all around the world, filmmakers have indeed adapted this unwieldy apparatus for the clearest expression of their innermost thoughts.

Let’s return to the claim that this type of personal filmmaking, this “cinema of me” is also always a “cinema of we.” So many of the themes developed in the films of this program manage to touch on universal themes, transcending even while displaying their own limited cultural milieu or personal preoccupations. When Pawel and Marcel Lozinski head out on their father-and-son road trip that exposes the unresolved pain in the wake of a harrowing divorce, we’re suddenly not in a car driving in Poland but in our own memories and experiences of the brokenness of nuclear families. And if we have never experienced the divorce of our parents or the loss of a family member, or the displacements and traumas of war, we’re fortunate to have these talented filmmakers using all of the creative means at their disposal to communicate something of those experiences to us.

Even when the theme couldn’t be more myopically focused, as with Viktor Kossakovsky’s Wednesday, about people born in Leningrad who share the same birthday as the filmmaker, the themes that emerge are nothing short of existential: the meaning of existence, the randomness of birth, the belief systems surrounding questions of fate are all contemplated by the quirkily untutored participants in this film. Distance, alienation, loneliness, fear of abandonment, exile and loss are themes that run through many of the films in this selection—themes that resonate well beyond the intimate concerns of the filmmaker him or herself.

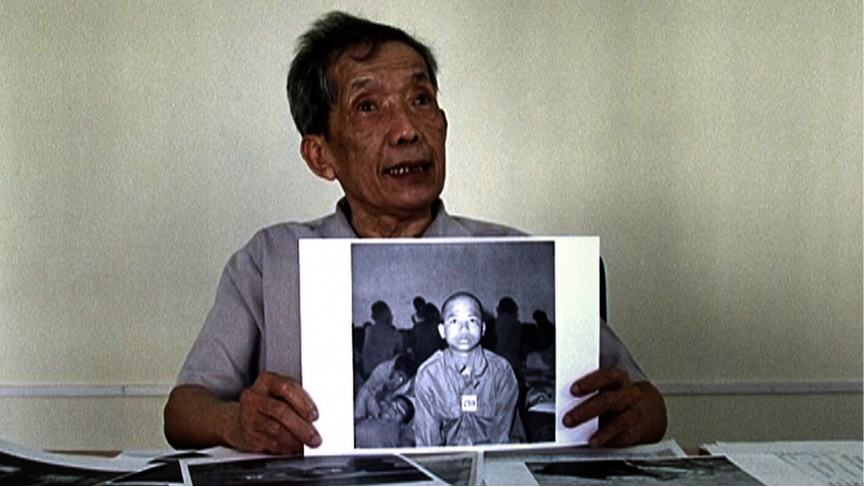

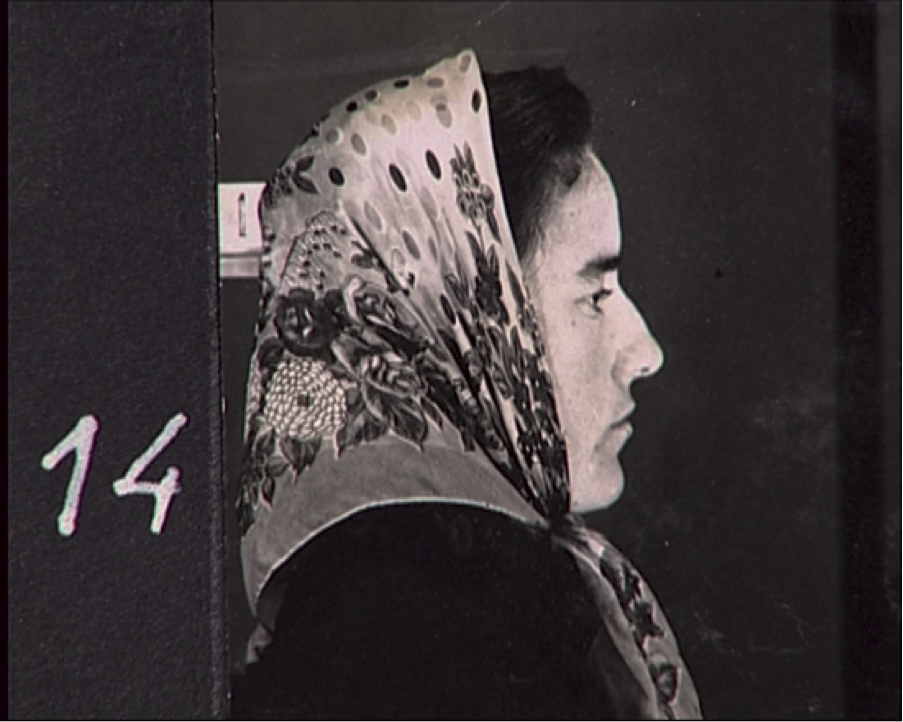

Some of the filmmakers featured in this section are inveterate first-person filmmakers. Ross McEllwee, for instance, made his presence behind the camera a signature of his filmmaking practice, from the time he made Sherman’s March in 1985 right up through today. Avi Mograbi in Israel and Andrés Di Tella in Argentina are also mainly known for their first-person films. Others, like Naomi Kawase or Chantal Akerman, contribute important films in this personal vein but are better known for their fiction films. These may traverse some similar themes, but they don’t necessarily make the filmmaker’s personal story explicitly evident. Rithy Panh, for his part, has made several documentaries and a handful of fiction films, but The Missing Picture and his new film, Graves without a Name, are by far his most personal films, depicting his memories of life and death under the Khmer Rouge. For Panh, in line with the majority of the filmmakers included here, the first-person address is reserved for those films that simply couldn’t have been made otherwise. It’s much less a question of self-indulgence, and much more the urgency to communicate a complex formative experience (very often a trauma) that leads a filmmaker down this path. These are films that were burning to be made, and the experience of watching each and every one of these films forged in the furnace of the soul, makes a deep impression on us. These films aren’t easily forgotten, so come prepared to be profoundly affected.

Alisa Lebow contributed to IDFA’s focus program "Me" as senior advisor and interviewed some of the filmmakers in the program during the festival. In addition, Lebow was a member of the IDFA 2018 jury.

November 2015

INTRODUCTION FOR A SPECIAL ISSUE OF ALTYAZI ON THE WORK OF CHANTAL AKERMAN

It is with a very heavy heart that I write this introduction. Chantal Akerman is a filmmaker whose work I have loved and admired for several decades. In the many eulogies and obituaries that have come out since her untimely death on October 5th, there is one sentiment that consistently comes across: the deep and lasting impression her films have made on so many of us. Her films were not for all tastes, her unadulterated vision was too strong for some, but for those of us whom she touched, she did so in an indelible way.

...

Akerman

was a prolific filmmaker, often working for television in between her larger

projects, and always experimenting with form. She made feature length fiction

films, shorts, experimental films, documentaries, and in the last 20 years, she

made several forays into the world of multi-channel installations for galleries

and museums. While some have tried to force her into categories, whether based

on her multiple identities (Jewish, lesbian, feminist, child of holocaust

survivors), her gender (female), or her filmmaking inclinations (minimalist,

structuralist), these have always failed to encompass the breadth of her work

and as she actively opposed any categorization other than ‘filmmaker’ in her

lifetime, I believe we should respect her rightful resistance and remember her

as what she was, a great filmmaker, full stop.

I

was introduced to her work in a film class in 1983, where we watched her magnum

opus, Jeanne Dielman: 23 quai du Commerce

1080, Bruxelles, a film she made in 1975 at the age of 24. Jeanne Dielman is an unforgettable film,

not only for the experience of duration, which, at 3 hours and 45 minutes, can

be challenging in the extreme, but for its bold reinterpretation of domestic

time as worthy of representation, and for the unflinching directorial style. With

uncompromising attention to the slow, precise, rhythms of everyday routine, the

film has the structure of an inverted thriller, every bit as knuckle-whitening

as a fast-paced action film, only in reverse. Few filmmakers before or since

have been as brave and forthright in their cinematic language. Once you

acclimatize to Akerman’s sense of timing and indeed her dry humor and off-beat

sensibility, it becomes something like a drug. You seek it out in other

filmmakers’ work and when you can’t find it, you turn back to her with great

longing and affection. To say that Akerman was a singular voice in cinema is

simply to state a fact. To place her alongside the other cinematic greats of

her generation (Godard, Fassbinder, Herzog) is to redress an historical

injustice, as her work is every bit as innovative and important in the history

of cinema as theirs, though she remained undervalued and under-recognized to

the end.

Her

films are too many to mention here, but I will review what are the highlights

for me in her impressive, nearly 45 year, career. Her first film, Saute ma ville, was an unstudied send-up

of domesticity, the lead part played with Chaplainesque impishness by an 18

year old Akerman herself. She plays the lead in her first feature as well, the

impressive Je, tu, il, elle (1974), which she made only a year before Jeanne Dielman, and while less formally

ambitious, it is just as taboo-breaking and memorable in its playful expression

of a young woman’s independence and desire. We see hints of the feisty mercurial

lead character again in two shorts she made a decade apart, J’ai faim, j’ai froid (1984) and the

bewitching Portrait d’une jeune fille de

la fin des anées 60 à Bruxelles (1994).

Her

experimental film work of the early and mid-1970s was heavily influenced by the

structuralist filmmaking of Michael Snow and the personal, almost home movie, style

of Jonas Mekas. Yet her original voice as a filmmaker, literally and

figuratively, comes across very clearly in her New York films, News from Home and Hotel Monterrey. News from

Home, in particular, takes up many of the themes we find in her later work:

nomadism, the fascination with the everyday, the imbricated lives of mother and

daughter, the way in which history haunts the present. The exquisitely

restrained camera work of one of her early collaborators, cinematographer

Babette Mangolte, is one of the highlights of this film.

Akerman

went on to make 12 more feature films and half as many feature length

documentaries, the most memorable for me being D’Est, a film that comprised one part of her very first museum

installation, Bordering on Fiction, which

premiered at the Walker Art Foundation in Minneapolis in 1995. D’Est is a return to Akerman’s extreme

long takes and her interest in the quotidian, yet it is also another form of

‘return’, where she in effect retraces the steps in reverse of her parents’ exile

from Eastern Europe during WWII. Shot just after the fall of the Berlin Wall,

it is at once a study of that present moment of transition and of the traces it

still bears of the past. Akerman eschews archival footage and narration,

counting instead on the penetrating gaze of her insistent camera to yield the

insights of history for those patient enough to watch. With this installation,

she began to explicitly revisit her Jewishness, not out of any particular

religious conviction, but from the weight of its history as it pressed upon

her.

Not

all of Akerman’s experiments were a success, and when she failed, she failed

spectacularly, as with the one and only mainstream film she endeavoured, the

$10 million dollar box office bust, A

Couch in New York (1996), starring William Hurt and Juliette Binoche. The

plot was simple enough and the characters well chosen for what was essentially

a quirky romantic comedy. Yet Akerman’s irrepressible spirit forced an

awkwardness and a just-off-the-mark sensibility that was too subtle for the

film’s mainstream pretensions, and not pronounced enough for her experimental

fan base. The film found its way to the graveyard of the cinema, where it

surprised me more than once, first on an overnight bus from Bodrum to Istanbul

and later on a transatlantic flight back to New York. I watched it all the way

through both times, happy to be accompanied by her spirit in the unlikeliest of

places. Although Akerman never worked with Hollywood again (or should I say,

Hollywood never worked with Akerman again?), she did make several other

relatively light-hearted features with mixed success, both before and after,

such as Nuit et Jour (1991) about a woman

dating two taxi drivers, one on the day shift, the other on the night shift, and

Demain on déménage (2004), about a

mother and daughter forced to live together after the death of the father. She

also made two more weighty, and much better acclaimed, adaptations, the first

of Proust’s La Prisoniere, in her La Captive (2000), and the second, of

Conrad, in La Folie Almayer (2012).

Akerman’s

work on the whole was so intricately intertwined with her life and her sense of

self that in 1997, when asked by Arte to make a filmic self portrait, she

responded by making a film that, with the exception of a somewhat rambling and

artless straight to camera introduction by Akerman herself, was comprised

exclusively of footage from her films. In effect, she was saying, look to my

films if you want to know anything about my life, it’s all there. Indeed, Akerman

is one of the most personal directors we have ever encountered in the cinema,

the force of her vision and personality, as well as her recurrent obsessions

and tropes, form an integral part of the experience of her work. One feels, the

more one gets to know her work, the better one knows her, to the point of

making her death feel very much like a personal loss.

Akerman,

a life-long sufferer of depression, died at her own hand, only a year after she

lost her mother, a holocaust survivor whose simple life as a petit-bourgeois

housewife in Brussels was at the center of inspiration for most of Akerman’s

work. It’s as if with her mother/muse gone, there could be no more reason to go

on. Life, for her, seems to have become unbearable. Yet I remain grateful at

least, that her films remain and perhaps more than any other filmmaker I can

think of, she lives on for us in her films.

London Dispatch

2007-2012

For 5 years I wrote a monthly column on all things ‘documentary’ for the Turkish film magazine, Altyazı. I wrote the column in English and every month generous friends would translate it into Turkish for me. Here, for the first time, they are all available in English as well.

London Dispatch #58 – December 2012

TURKISH ENglish

Terra de Ninguem/No Man’s Land (Salomé Lamas, 2012)

Lisbon has two major annual

film festivals, Indielisboa, and Doclisboa. The fact that there is no major

mainstream film festival in that city is already a sign that it’s not your

average film-town. The fact that their documentary film festival is one of the

major events of the year, with packed theatres throughout the ambitious 10 day

event, is another. This year I was fortunate enough to be invited to serve on

the New Talent jury (one of four juries convened), which meant that while I

couldn’t see all of the films I had ticked on the program, I did get to see

some of the freshest talents coming out of the documentary world. We were

tasked with giving two prizes, one for an emerging Portuguese filmmaker and the

other for an international emerging filmmaker. I won’t try to enumerate all of

the 14 films we judged, but I’ll tell you the highlights.

Although we didn’t end up

selecting Ben Rivers’ Two Years at Sea it

was a strong contender. Rivers is actually a well known experimental filmmaker

in the UK who has made many short films, but as this was his first feature

length film and the competition was only for features, he was eligible for this

prize. Rivers shoots all of his work on film, in black and white, harkening

back to not only another time in film aesthetics, but in the world. This

feature, which observationally documents a current day Scottish hermit, could

have been shot any time in the last 50 years, dated to the present only by a

brief glimpse of a recent model 4x4. The film’s ethereal timelessness, and

indeed the alternative model of time as measured only in increments of need

(cooking, washing, eating, sleeping) and desire (listening to music, reading)

rather than the instrumentalist temporality the rest of us have gotten so used

to, is precisely its power.

The other film to mention

before discussing the prize-winning films is, Captivity (André Gil Mata),

a quiet meditation about the young filmmaker’s dying grandmother. It begins in

the hallway of a stately village house with the sound of belaboured breathing

groaning loudly on the audio track. The filmmaker longs to capture some sign of

recognition from this elderly matriarch as she in turn is involved in the

all-consuming effort to cling to the last gasps of life. She is captive in the

house, in her body, in the echo chamber of her own lungs, and the overwhelming

sense of the film is one of claustrophobia, effectively communicated through

acute observation and astute personal voiceover narration. It’s a slow but

moving gem.

I’ve no doubt these films

would have won, had not these other two been in the competition. The film that

won the Portuguese prize was Terra de

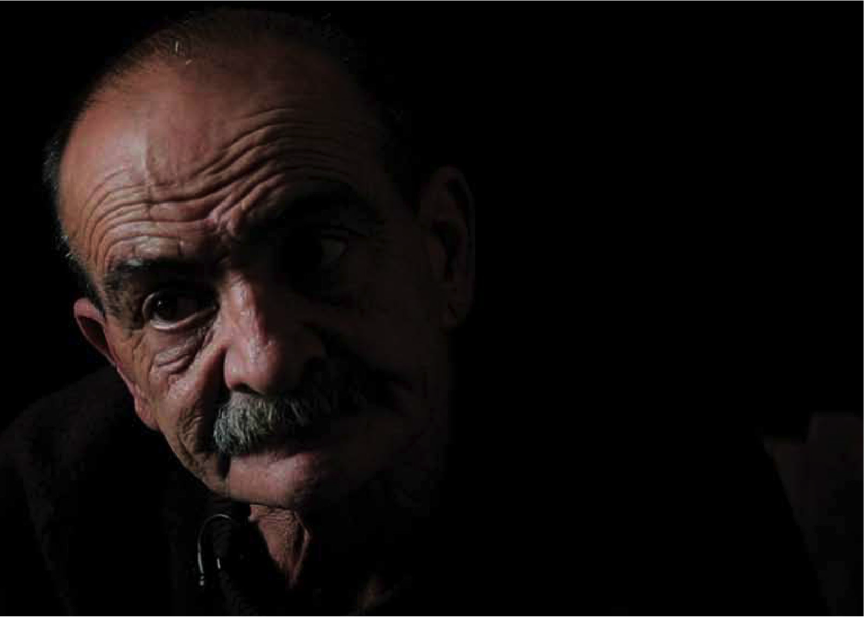

Ninguem/No Man’s Land, by Salomé Lamas, a nearly pure talking head

interview film, bringing us face to face with Paulo, a shady but thoroughly

compelling character, who spent most of his working life as a mercenary

assassin working for the Portuguese government, the CIA, and other equally

nefarious ‘clients’. His story, if it is indeed even true, details the shadowy

outlines of official history, the counter-insurgent movements in the former

colonies, the para-military exercises in Latin America, and much more. His

chronology seems to roughly coincide with official history, and the story is

verifiable except that this man seated before us has no registered documents,

no address, no official identity. Like any good assassin, he leaves no trace.

Leaving aside the vexing question of veracity, it is the identificatory

feelings that this figure awakens that makes this film so disturbing. The

documentary spectator is well versed in identifying with the victim and

witness, but is much less prepared for the disturbing experience of identifying

with the perpetrator.

The other prize-winning film was called Espoir Voyage (Michel Zongo) perhaps the

first film I have ever seen from Burkina Faso. Zongo attempts to find the trail

of his brother, who died as an economic migrant working in the cocoa fields of

neighboring Ivory Coast when the filmmaker was only 4. A road movie with a

quest, the structure is familiar, even if the characters, the vehicles, the

conditions of movement and statis revealed in this film are not. A better

testament to why and how self-representation can be the best antedote to the

oversimplifying and condescending gaze of the colonizing other could not be

found. I look forward to seeing more from this filmmaker to be sure.

London Dispatch #57 – November 2012

TURKISH ENglish

*

Last month I wrote about a stunning, mind-boggling film, The Act of Killing (Joshua Oppenheimer,

Christine Cynn, Anonymous, 2012), which by the way, I have reason to believe

will be in one of the big Istanbul film festivals next year. This month, I’m

thinking about quieter films, films that are not flashy or showy, and may even

require some real patience to watch. I often find myself watching films that I

think are really important and wish people would see, only to reflect upon how

difficult the film might be for most people to sit through. The most recent

film of this kind that I’ve seen is an Israeli film called The Law in These Parts (Ra’anan Androwitz, 2011).

Granted, this film is not doing badly on the festival circuit.

It did win, after all, the World Cinema Jury Prize for Documentary at Sundance,

and several other prizes as well. It’s an incredibly well crafted film, shot

beautifully, and structured reflexively, featuring a thoughtful and

well-executed first person voiceover track. But it’s a talking heads film, with

interview after interview with geriatric judges, all of whom at one time or

another presided over military courts in Israel’s occupied territories. They

speak legalese, for pity’s sake. And they’re each, in his own eloquent and

erudite way, justifying their miscarriages of justice. The only sympathetic

voice to grab hold of is the disembodied voice of the filmmaker, who one

somehow feels is on the side of justice, when all these other embodiments of

the law are not. This is not a film for the distracted. You must concentrate

hard. Listen and parse every word. A degree in Israeli and International Law

could be of some use as well.

Still, it’s a film I wish everyone would watch. One can learn so

much about how reasonable people can act unreasonably, how the law itself can

be interpreted with so little impartiality, what crimes can be committed and

justified in the name of ‘democracy’ and ‘security’. These are certainly

buzzwords that have relevance outside of the Israel/Palestine conflict. There

is no one on this planet who is not in some way implicated in these discourses.

Yet, I wonder, and worry, who, besides documentary nerds like myself, has the

patience to listen?

I remember feeling similarly when I watched The Corporation (Jennifer Abbot and Mark Achbar, 2003). I thought

then, as I do now, that the film should be required viewing for every school

child in capitalist countries. But the film is so didactic and overly-long,

that I remember being actually angry with the filmmakers for making it nearly

impenetrable for the very people who needed to see it (i.e., everyone). Again,

that film has not been unsuccessful. As documentaries go, it has had quite a

good run, winning countless awards, going on theatrical release, and claiming

on its website to be ‘Canada’s most successful documentary…EVER’. I’m sure

that’s true. But when I say I think it should be required viewing, I have in

mind people like my students at Brunel, who I can guarantee you, have never

heard of it. And need to.

I suppose I have set my hopes too high. Both films mentioned

have had real success and will continue to be screened and seen. This is more

than most documentaries can ever hope for. But without the Busby Berkeley on

acid numbers seen in the Act of Killing,

they will never be big hits, promoted by Errol Morris and Werner Herzog,

written about by Zizek, on the tips of the tongues of all who have seen it.

They will remain important, serious, essential viewing, that sadly, many may

miss.

Note: Zizek recently wrote

about this film online here.

London Dispatch #56 – October 2012

TURKISH ENglish

The Act of Killing (Joshua Oppenheimer, 2012)

A documentary that recently premiered at the Telluride Film

Festival, moving quickly on to Toronto, is about to take the documentary world

by storm. I’m not one to make such predictions lightly, and of course, I could

be very wrong, as the film in question is so brutal, so demanding, and so

beyond anyone’s wildest nightmares of what could be, that it may truly be too

much for audiences and critics alike. But suffice it to say, I've never seen

anything like it.

Its title, The Act of

Killing, may seem anodyne at first. But given that it’s a film that

features actual Indonesian death squad leaders, not only re-enacting their

gruesome ‘acts’ for the documentary’s camera, but also ‘acting’ in their own,

fantasy-musical-gangster film that they’re making about their unusual lives,

the title is apt. The Act of Killing

would be powerful enough if it only documented the lives of these frightening

men. But this film goes further, with a film within a film structure, and

completely outlandish representational strategies (the gangsters film

themselves in garish Technicolor in fantastical tropical sets that even Busby

Berkeley could not have conceived), giving it an otherworldly quality, rarely

if ever found in all but Herzog or early Errol Morris documentaries.

Indeed, it is clear that both Herzog and Morris found a kindred

spirit in director Joshua Oppenheimer (the film is credited with three

directors, one anonymous, and the other, Christine Cynn, who was more involved

in earlier phases of the production), as they both signed on as executive

producer. Herzog is quoted on the film’s website as saying: “I have not seen a

film as powerful, surreal, and frightening in at least a decade.” Morris

actually introduced the film at Telluride. He says: “Like all great

documentaries, The Act of Killing

demands another way of looking at reality. It starts as a dreamscape, an

attempt to allow the perpetrators to reenact what they did, and then something

truly amazing happens. The dream dissolves into nightmare and then into bitter

reality. An amazing and impressive film.”

Imagine a world where

gangsters rule, running all of the state institutions, celebrating their

achievements in rallies and on tv. I don't mean politicians who behave like

gangsters. I mean cruel, uneducated, petty criminals who were recruited by the

regime 45 years ago to commit extrajudicial killings of hundreds of thousands

of fellow citizens with their bare hands, and then spending the last nearly

half century getting rich and accruing power and bragging boldly about their barbarous

acts. This film is shot in Indonesia, a country that has never had to reckon

with its bloody past, as the brutal victors remain in power. The only

comparison I can make would be if the Nazi's had won the war, and Auschwitz had

become a model for how to deal with society's 'undesireables.' In other words,

the world in the film is the world turned upside-down and inside out. We spend

time with these men, but thankfully are never asked or expected to love them.

Nonetheless, they force us into an encounter with power that is unvarnished in

its façade, raw and unstoppable. Any thoughts of a world where there is the

rule of law, codes of ethics, basic shared notions of civility and decency, is

just a dream; the film reveals the stark reality. And despite the hot pink

aesthetics that would make John Waters proud, the truth that it shows, is far

from pretty. The fact that, as Morris suggests, the dream begins to unravel

towards the end, does nothing to undo the unnerving experience of having seen

hell and understanding that it’s right here on earth. Any film, documentary or

otherwise, that can do that, deserves to be called a masterpiece.

London Dispatch #55 – September 2012

TURKISH ENglish

Sans Soleil (Chris Marker, 1982)

This summer the documentary world lost two of its most visionary

contributors, one known to all students of documentary and experimental film,

the other somewhat less well known, but no less influential or beloved. The

first filmmaker I speak of is Chris Marker, the maker of legendary films such

as La Jetee and Sans Soleil, who died on his 91st birthday, 29 July

2012, and the other was a teacher of mine (and countless others) at NYU, George

Stoney, who died on 12 July, just 12 days after he turned 96. Both were

prolific filmmakers, lifelong leftists, and new media advocates well before it

was fashionable.

Chris Marker was a pseudonym, his real name was Christian

François Bouche-Villeneuve, and lore has it he chose his nom de plume based

literally on the name of a pen: the ‘magic marker’, and indeed he used the

filmic medium much in the way advocated by Alexandre Astruc, as a ‘camera

stylo’ or camera-pen. He is credited for having innovated the film essay as a

form, an early example of which would be his Description d’un Combat/Description of a Struggle (1960) which

while remarkable structurally and stylistically, displays an enthusiasm toward

the young nation of Israel that could only be expressed by a leftist—one who

fought in the French resistance in WWII -- in that era. Later there was a

wonderful, if somewhat wry, return to this film by Israeli filmmaker Dan Geva,

with his homage to Marker, Description of

a Memory.

Probably Marker’s most famous epistolary film essay is Sans Soleil (1982), where he invents the

character of Sandor Krasna, an inveterate wanderer whose ‘letters’ are read by

an unidentified and insouciant female narrator. Both Krasna and the narrator

serve as alter egos of the filmmaker, and with these clever devices, Marker

managed to challenge the two central tenets of documentary: authorship and

authenticity. A later film essay of Marker’s, The Case of the Grinning Cat (2004), takes a meandering course through Marker’s beloved Paris following

the random appearances of a mysterious graffitied Cheshire, observing the

city’s present day as it resonates with his memories of poetry and activism in

Paris from days past. Considering the filmmaker was 83 when he made the film,

it is remarkably fresh, playful and sharp-witted, as if made by a giggling

sage.

George Stoney made almost as many films as Marker, though very

few of them ever became well known. Probably his best-known films were All My Babies (1953) a legendary

training film about midwifery in the American South that was used for years by

the US National Institute for Health, How

the Myth Was Made (1978), a film uncovering the omissions and manipulations

in Robert Flaherty’s classic documentary Man

of Aran (1934), and Uprising ’34

(1995) made with Judith Helfand and Susanne Rostock, about the cotton mill

worker’s strike during the ‘Great Depression’ in the US. Uprising ‘34 was another myth-breaking film, this time debunking

the certainty that the US Southern workers were always hostile to union

organising.

But truth be told, George Stoney will be better remembered as a

teacher and organizer than as a filmmaker. As a professor at NYU for over 40

years, he taught generations of filmmakers and film scholars (including myself)

how to make sensitive, thoughtful, politically engaged documentaries. He was a

gentle yet pragmatic teacher, ever encouraging, with a practical solution to

almost any film-related problem. As an organizer, he was one of a small group of

media-activists that started the first ever ‘public access’ channel on US cable

television in 1970, envisioning in that technology the potential for local

organizing that has finally been realised even more fully via social media. In

an interview he gave recently he said: “We look on cable as a way of

encouraging public action, not just access…It’s how people can get information

to their neighbors, and their neighbors can get out on the streets to

organize.”

Both Marker and Stoney

embraced new technologies and media while never abandoning their initial aims

and hopes for the medium they left endlessly enriched by their contributions.

These two indefatigable giants—neither of whom ever stopped making films or

encouraging others to do so— will be sorely missed.

London Dispatch #54 – July 2012

TURKISH ENglish

Capturing the Friedmans (Andrew Jarecki, 2003)

When Capturing the

Friedmans (Andrew Jarecki, 2003) first came out, it was a big hit, not only

on the festival circuit (it won the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance that year),

but theatrically as well. It was one among a string of documentaries in the

early 2000s to prove that documentary can have popular appeal. What I notice

nearly ten years later, upon rewatching it, is that it is a rare ‘popular’

documentary that neither dumbs down its presentation, nor capitulates to the

over-simplifying formulae of popular genre.

It is, most definitely, a genre film, a ‘who dunnit’ crime

mystery to be more specific. For those who haven’t seen it (and I highly

recommend that you do), the film is about a middle class suburban American

family in the 1980s, embroiled in a scandalous trial over paedophilic acts that

allegedly took place during afternoon computer classes for children. The late

1980s was a time of rampant hysteria about paedophilia in the US, a frantic

wave that seems to have spread to England shortly thereafter. This mass

obsession seems to have generated a spate of ‘cases’ rather than the other way

around. That is to say, it’s unclear that paedophilia was on the rise at all,

but instead, the agitated discourse around it seems to have conjured up a

collectively imagined epidemic, shored up by questionable police tactics and

legal procedures, not to mention frenetic media coverage.

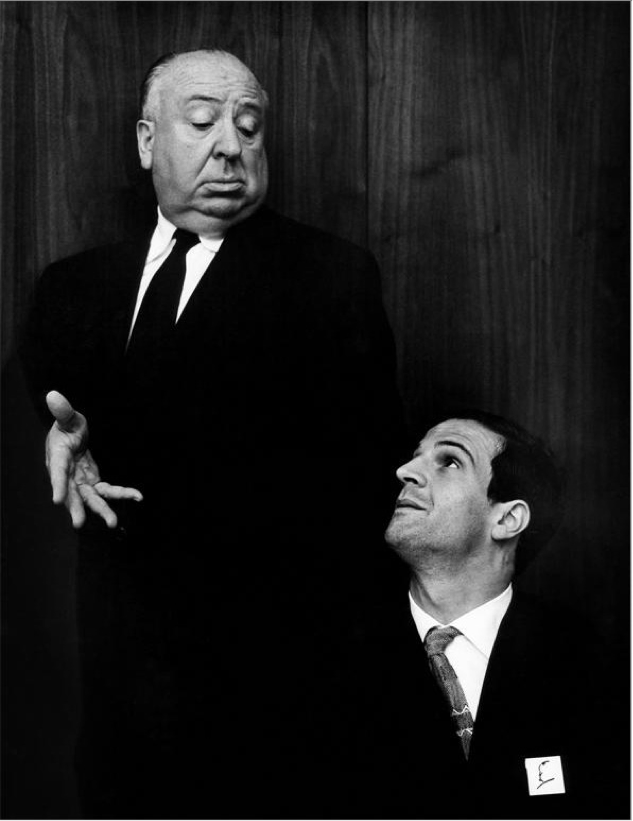

What’s fascinating about the film is not so much the way it

conveys the zeitgeist of the times, but its way of managing the material.

Arguably, the last time a film had so destabilized the certainty and security

of the viewer, was in 1960, when Alfred Hitchcock knocked off his leading lady

less than ten minutes into Psycho, as

the character, Marion, with whom we identify as our narrator, dies a horrible,

screeching, death in the shower. That feeling of having nothing but the flimsy

shower curtain to cling to for guidance is hinted at in Capturing the Friedmans, where we are meant to simultaneously hold

in our minds the fact that the pater familias, Arnold Friedman, a seemingly

sweet and caring father, unassuming and unexceptional in every way, is an

admitted paedophile who, nonetheless, likely did not commit the crimes for which he was accused.

There have been many articles written since the film was

released, lamenting the fact that Jarecki was not more emphatic in his support

of Arnold’s innocence and the clear manipulation of facts and evidence by the

police, not to mention the bias of the judge, who declares in the film that she

was convinced of the accused’s guilt right from the start, a shocking admission

from a jurist who is sworn to uphold the principle of ‘innocence until proven

guilty’. And while there are clear cases of documentaries that have served to

redress injustice within the legal system—the most famous is Errol Morris’ Thin Blue Line (1989) which was credited

with reopening a capital punishment murder case that had the wrong man on death

row — I believe Capturing the Friedmans

does something equally impressive, by refusing to settle on simple fairy tale

truths of ‘guilt’ or ‘innocence’. The law itself, the very system designed to

give unambiguous verdicts, in this film, is revealed to be nothing more than

compromised bargains reached in backroom negotiations with slippery lawyers.

While the squabbling family

unravels in front of the camera under the probing reach of search warrants and

the hostile treatment in the press, it is not just the individual members that

appear to be unbalanced, but the scales of justice as well. I think the

greatest achievement of this film is to turn the tables back onto the viewer,

who finds herself endlessly shifting positions, never knowing finally who is to

blame or where the truth lies. In that process, we can’t help but notice that

the role of judge and jury is one we play all too eagerly when watching a

documentary, despite the fact that films are not actually evidentiary of

anything other than the filmmaker’s point of view. If Capturing the Friedmans captures anything at all, it is the viewer,

who is caught in the act of trying to pronounce judgement based on what we’re

given in a film. If a spectator can leave that film realising how ill equipped

s/he is to play the role of moral arbiter, then Capturing the Friedmans will have succeeded in challenging the

unwarranted ‘superior’ position of documentary spectatorship better than any

other documentary I can think of. It is for this, and for its commitment to

ambiguity and complexity in the face of, not despite, the ‘facts’, that this

film deserves to be remembered.

London Dispatch #53 – June 2012

TURKISH ENglish

5 Broken Cameras (Emad Burnat and Guy Davidi, 2011)

I’ve been thinking about the boycott of Israel that has been

going on since 2005 but has gained momentum in the last few years. It is a

coordinated call for economic divestment and sanctions against Israel, which I

support, but as with the South African Apartheid model upon which this one is

based, the boycott is not only economic but also cultural. This is complicated,

of course, but the main aim is to raise awareness of the issues and to garner

enough international pressure, both economic and moral, to bring Israel in line

with international law with regard to the occupation of the West Bank, Gaza and

the Golan Heights. Because this boycott is in effect, when Madonna agrees to

perform in Israel, she sets off a negative PR campaign that allows activists to

further publicise their cause. Similarly, when the Israeli Habima theatre

company is invited to perform Shakespeare in Hebrew at the Globe Theatre in

London, again the call is loud and clear to boycott. Why boycott Habima

theatre? Not because they would perform Shakespeare in Hebrew, but because they

receive government funding and perform in the illegal Israeli settlements on

the West Bank. So far so good.

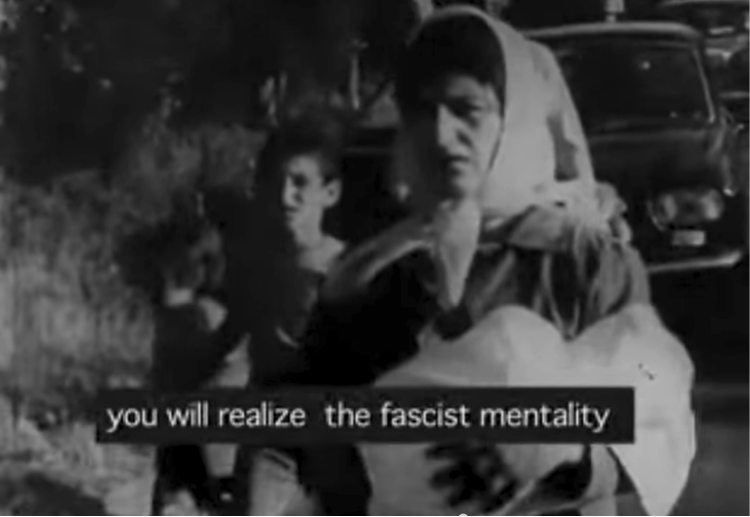

It’s only when I sit down to watch a gut-wrenching documentary

made jointly by a Palestinian and an Israeli, funded by many sources including

several Israeli funds, that I start to have my doubts. 5 Broken Cameras, by Emad Burnat and Guy Davidi (2011) has not been

boycotted that I know of, in fact it has won several prominent international

awards, and for good reason, I’d say. Despite it having been cultivated in the

Israeli-funded Greenhouse project, and receiving funds from both the New

Israeli Foundation for Cinema, and the Israeli Film Council, it is a film that

deserves to be seen. Not only does it document 5 long years of resistance

against the building of the separation wall near the village of Bil’in, but it

does so from a Palestinian perspective that evocatively communicates the

relentless brutality and injustices perpetrated by the Israeli military in the

process.

Some might say this only serves as positive press for Israel,

demonstrating its catholic tolerance of different perspectives in a truly

democratic gesture, but I don’t see how allowing the wanton attacks against

innocent Palestinian civilians to be seen, as they attempt to protect their

livelihood and families, could ever be spun to show them in a positive light.

True, the film has not been censored by the Israelis, but rather than that

being a feather in their cap, it should merely serve the function of free

speech (intermittently practiced at the best of times), which is to present

dissenting opinions to those who should most be exposed to them. I watched the

film trying to imagine an Israeli audience being confronted with its

government’s blatant double standards and outrageous flouting of international

law, and thought, good, let them see. The fact that it is a co-production can

only serve to make its message more effective for that audience.

It’s not that the film is without problems. The

filmmaker/protagonist is avowedly pacifist and his political positions are in

some sense beyond reproach. He is portrayed as Mr. Clean and one wonders if

this film would have ever been made if he had, for instance, even for a moment,

entertained the idea of violent retaliation or ever expressed a single

prejudiced thought. He is, in a sense, a model Palestinian, and that is in and

of itself offensive. Still, as the actions he videotapes attest, the movement in

Bil’in was avowedly non-violent, despite the overt violence and prejudice they

faced, and that too deserves to be shown.

My question here has to do

with the boycott though. If I wouldn’t want this film to be boycotted, and if I

feel it has important cultural and political work to do, then how can I support

the boycott otherwise? A boycott needs to be consistent and uncompromising. If

I protest one project for taking Israeli government funds, then I have to

protest them all. Yet a film like Five

Broken Cameras puts a dent in my certainty. I’m glad it was made and I’m

glad it is being seen. So much for categorical thinking.

London Dispatch #52 – May 2012

TURKISH ENglishA friend of mine recently left journalism to make documentaries

for a well-known news and information television channel. She confided in me

that she’d like to take one of my documentary classes, as although it’s now her

full time job, she actually knows very little about the form. Most of her

journalistic experience was in radio and print, and translating her ideas to

the audio-visual medium has proven a challenge. This confirmed my suspicions

that those who hire television documentary producers expect little more than

illustrated radio-plays, with no intention of either training their staff in

the craft of filmmaking or prioritizing the visual elements of good

storytelling. Having some experience years ago making short ‘documentaries’ for

television, I’ve often repeated to my MA students that if their greatest

aspiration is to make tv documentaries, they really didn’t need to be on our

course, as the training we give would be superfluous to the demands of the job.

If you have an idea, know how to research it, and can work with a camera crew

to get your interviews lit and in focus, then the rest is really just by rote.

In fact, most tv documentaries are so formulaic aesthetically (interview,

supporting archival footage plus other illustrative visual material, maybe

voice over narration) that if you’ve watched a few and understand the basic

principles, any semi-intelligent person could do it. Who needs to spend

thousands of pounds to study that which you could better learn ‘on the job’?

Not that there’s anything wrong with aspiring to make television

documentaries. They are, after all, the most familiar form of documentaries

known to audiences, not to mention one of the very few ways one can make a

living in the field. You can have an interesting life and feel that in some

sense you are contributing to the circulation of knowledge, informing possibly

millions of viewers at any one time. As jobs go, it’s pretty sweet. The problem

is, firstly, that these films are just content filler for television’s

insatiable programming needs, not for the most part, memorable or important

films. Secondly, there are fewer and fewer such jobs, as television tends to

‘outsource’ its documentary making to independent filmmakers, only buying the

projects once they’re finished, thus not taking any risks along the way. Most

stations and networks have only a few on-staff documentary producers, as it’s

much more cost-effective to buy the finished product. That means that

independent documentary production companies are often using their resources to

make films they believe television will buy, tying up potentially talented

independent filmmakers’ time producing middle-of-the-road television.

Ironically, I have many

students who come to do their MA in documentary practice with us precisely

because they’re tired of making television documentaries. They sense there’s

something more to the form, but haven’t had the opportunity to explore what

that might be. I wish I could offer classes, workshops, intensive sessions to

everyone who wants, on the aspects of documentary that people don’t otherwise

get exposed to—everything from observational, first person, essay, experimental

and lyrical docs, to the wonderful hybrids that integrate fiction in uncanny ways.

There are so many films I would want to show, so many techniques to talk about.

And maybe then people would understand the craft that goes into really great

documentary, and the art of it. Maybe then, we wouldn’t hear questions like I

heard at the world premier screening of Belmin Sonmez’s film Simdiki Zaman, at the Istanbul Film

Festival this year insinuating that a documentary filmmaker, naturally, wants

to ‘graduate’ to making fiction films. Maybe then, we might see more truly

innovative and challenging documentaries coming out of Turkey, rather than

people thinking they need to do their creative work in a different form. Why

can’t we take our lessons from masters like Kiarostami and Panahi in Iran,

Varda and Marker in France, or Herzog in Germany, who show us that the

documentary form has infinite potential to be great and inspiring art. Maybe

then we’d see fewer dull docs and more memorable films that we’d be proud to

call documentary.

London Dispatch #51 – April 2012

TURKISH ENglish

1+8 (Angelika Brudniak and Cynthia Madansky, 2012)

In this

world of global crossings, what does it mean to call a category of films ‘domestic documentaries’? Once upon a time one could

imagine it to have been a relatively clear-cut category, where if a citizen of

Turkey or someone of Turkish descent either produced or directed a film, then

it was ‘domestic’. But what if a film is

produced by someone from Turkey but directed and shot by a Nicaraguan, in

Nicaragua, about Nicaraguans, as happened with a spectacular film submitted

this year to the İstanbul

Film Festival domestic category (A Life

without Words, Adam Isenberg, produced by Senem Tüzen, 2011)? Can

we still consider that film domestic, due only to the presence of a producer

with a Turkish name? Or another film, which was not initially considered

domestic because the director/producer team, though both living in İstanbul for many years, were

not from Turkey, despite the fact that the film concerns itself with the

decidedly domestic concerns of Turkey's multiple borders? This singular film, 1+8 (Angelika Brudniak and Cynthia

Madansky, 2012) throws all such overly simplistic national categories of

belonging into long-overdue crisis.

As I

understand it, every middle school student in Turkey learns of the unique

geo-political location in which Turkey finds itself, surrounded on all sides by

enemies, 8 in all. Had a state-school educated child made the film, it would

have been called 1 against 8, but luckily for us the filmmakers who made this

impressive meditation on life at the borders were clearly inspired by this

octagonal regional positioning and all of its complex cultural, economic,

linguistic, and of course political, consequences. For Brudniak and Madansky,

the multiple points of crossing only add to the cultural weave of the land,

hence the 'plus' in the title.

The

border turns out to be an ambitious and fascinating subject—a visceral political history

lesson told on a human scale. Broken down into eight parts, each section of the

film visits both sides of a given border region. Brudniak and Madansky’s camera makes no attempt to

be at home in its surroundings, never pretending to blend in, nor does it ever

exoticize or 'other' those caught in its gaze. There is a steadiness, an

equanimity, to the way in which the filmmakers look upon their subjects, with

the camera fixed in its place, allowing life to unfold before it. While the

actual border checkpoints remain out of view, the effects are deeply felt,

whether with the overbearing military presence in Silopi or the memories of

impermeable cold war boundaries with Georgia and Bulgaria. At points, Turkey

seems the luckier side, the wealthier, freer, more liberal if not liberated

option, whereas in others it plays the role of police state all too

convincingly.

Turkey

finds itself reflected back by people within its borders who feel themselves to

be outsiders as much as people across the border who are in many senses

related. The arbitrariness of borders (such as the one set up by the French

between Nusaybin and Al Qamishli, Syria in 1923 dividing families from their

relatives and farmers from their land) and the nonetheless hard-line policing

of them (anonymous Iranian voices tell us the 'imams' will shoot anyone dead

who tries to smuggle anything across the border) is one key theme that drives

this film.

The list

of credited interviewees adds several minutes to the length of the film,

testifying to just how many voices contributed to this multi-faceted portrait.

Some seen on camera, always framed frontally and centred, some just voices, we

hear people's heartfelt laments as well as some clearly rehearsed boilerplate

propaganda, signalling the censorious presence of a 'minder'. In film school

one is taught that a good interview is one where the interviewee is made to

feel at ease and free to recount. 1+8

exposes the fatuousness of this unquestioned 'virtue': it is precisely in the

stiltedness, the awkward and unnatural performances, that we are made to see,

feel, experience, the heavy hand of the state as it exerts inordinate pressure

upon the inhabitants of its circumference.

Never

descending into pat ethnographic clichés

nor seduced by sectarian rhetoric and animosities, 1+8 traverses contentious terrain with an abiding respect and love

that is palpable. The viewer sees the extremes in landscape, poverty, political

repression, while at the same time there is the recognition that even at the

limits of the land, life clings to its most basic human values, like lichen

clings above tree line to an exposed rock. It's all laid bare to see, for those

with the patience and willingness to look. 1+8

will be screened in the Domestic section of the İstanbul

Film Festival this month. A Life without

Words, also a brave and beautifully crafted film that takes us to the

frontiers -- in this case of human communication -- will be included in the NTV

Documentary strand.

London Dispatch #50 – March 2012

TURKISH ENglish

Rouge Parole (Elyes Baccar, 2011)

When the revolutionary spirit caught fire over a

year ago and started spreading wildly, I suppose I was not the only one glued

to the tv. But television news has its limitations, biases, investments, which

make it a less than satisfying way to hear the stories, learn of the struggles,

and indeed get a feel for the atmosphere of the events. Filmmakers and amateurs

alike grabbed their cameras in Tunis, in Cairo, all over, and some hastily

edited their footage into films. Others set up archives to gather all of the

materials, audiovisual and otherwise, of the revolution, to research, study,

edit, when the dust settles. Making sense of momentous events that transform so

quickly and have so many facets is no simple matter. Yet, international

festivals immediately began to request films to show. Imagine, Ben Ali flees

Tunisia in January 2011 and No More Fear (Mourad Ben Cheikh, Tunisia),

the first film about the Tunisian revolution, premieres at Cannes in May of the

same year. Mubarak resigns on the 25th of January, and Tahrir–Liberation Square (Stefano

Savona, Italy) premieres at Locarno Film Festival that August. Both of these

films will be shown in the upcoming Istanbul Film festival, in a program that

I’m curating under the auspices of docIstanbul, called ‘Filming Revolution’.

But we didn’t simply want to be one more

festival greedily demanding the impossible from filmmakers in this historical

moment. We wanted to create a program that could reflect on the question of how

one films revolution, what can be revealed in the moment, what needs time for

reflection, what is lost in the urge to produce quickly and what gained. I

began to look to the dynamic films of past revolutions, to bring them into

fruitful dialogue with those of the present moment. It seemed to me there is

much that can be learned. It is this conversation, these sets of questions,

that we will bring to the Istanbul Film Festival.

We’ve selected a handful of historical films

about revolutionary movements in the general vicinity of Turkey (Eastern Europe,

Asia Minor, North Africa) to screen up against films from the current

movements, especially in Egypt and Tunisia. Well known films like Battle of Algiers (Gillo Pontecorvo,

1966) will be screened as will lesser known gems from the region, such as the

Palestinian filmmaker Heiny Srour’s heady experimental docu-fiction feature

film about women’s participation in the Palestinian liberation struggle Leila and the Wolves (Lebanon/UK,

1984). A more recent film Orange Winter

(Andrei Zagdansky, 2007), tells the impressive and under-reported story

of the peaceful struggle that won a transition of power in the Ukraine in

2004-5. I thought it important to include a film from the Iranian ‘Green’

movement that emerged during and after the 2009 elections in Iran, yet in the

current political climate in Iran, finding a suitable film proved a challenge.

I found, however, an interesting film made by an anonymous Iranian filmmaker in

Paris, who is literally trying to piece together the puzzle of what happened based

on the clips s/he could find on YouTube. The result is the intriguing Fragments of a Revolution (2011), which we will screen.

The two films from Tunisia, Rouge Parole (Elyes Baccar, Tunisia/Switzerland/ Qatar, 2011) and No More Fear,

seen back to back, give a multidimensional view of the events leading up to and

following the fall of the Ben Ali regime. And the film we’ve chosen to depict

the events in Cairo, Tahrir-Liberation

Square, is a fascinating observational film by outsider Stefano Savona, the viewing of which makes one feel the force of Mubarak’s thugs and the

counterforce of ‘the people’ resisting with every means at hand, including

digging up sidewalk cobblestones as ammunition.

For this dynamic program, we are inviting

filmmakers, historians and film scholars from the region to give some

perspective to the program as a whole, and to discuss the pressing question

faced in these recent days, of how one films revolution.

London Dispatch #49 – February 2012

TURKISH ENglish

Tahrir 2011: the Good, the Bad, and the Politician (Tamer Ezzat, Ayten Amin, Amr Salama, 2011)

I wouldn't be the first or

last to note that 2011 was a year not only of unrest but of revolution. The

'Arab Spring' which looks increasingly misnamed, as if it would have better

been called the Arab Spring, Summer, Fall, and Winter or better yet, the

Regional Revolutionary Rollercoaster Ride, has inspired myriad filmmakers,

vloggers, and phone philmers to edit together clips into what sometimes amount

to roughly hewn documentaries, and other times, just fragmentary glimpses of

the times. With the technology that millions now have to hand, the impulse to

document becomes not only irresistible, but almost obligatory for those

present. Yet in the midst of the chaos that is political change, some

filmmakers have acknowledged the need to choose: Participate or film?

One Egyptian filmmaker has

gone on record to say he had to leave his camera at home in order to fully

participate as a citizen and activist for change. Wael Omar notes in a recent

issue of Dox that he knew countless

filmmakers who were shooting, and thus felt no need to add to the excess of

documentation, and despite his usual camera-ready stance, decided to put his

camera aside and be counted as one among the masses. It must have been a

difficult choice for him, but he rightly claims that making sense of events as

momentus as the overthrow of Mubarak and the shifting power dynamics that

ensued deserves time to reflect. He seems confident that he will be able to

access footage in the future and make a film that better represents the

complexity of events, with the benefit of hindsight.

Other filmmakers have had

exactly the opposite instinct and have whipped together films of the moment,

some of which truly give one the sense of 'being there', while clearly never

being able to step back to analyse the situation. There's one from Cairo called

I am in the Square (Olfat Osman,

2011), whose title tells it all. Another from Tunisia called Rouge Parole (Elyes Baccar, 2011), that

is more ambitious, giving the background to the events that the media was

unable to convey. A third, called No More

Fear (Mourad Ben Cheikh, 2011) also from Tunisia, manages to communicate

the extent of the repression at the hands of Ben Ali, and the elation of having

finally gotten rid of the repressive tyrant.

One

of the best films to come out of the 'Arab Spring' will be playing at IF this

month: Tahrir 2011: the Good, the Bad,

and the Politician (Tamer Ezzat, Ayten Amin, Amr

Salama, Egypt, 2011). Still a film made very much in the midst of

the revolutionary fervor, with little to say about the subsequent course of

events that certainly complicate its unvarnished enthusiasm, it is nonetheless

a cleverly crafted and provocative documentary. Made in one month, in the

immediate aftermath of the overthrow, it is the work of three filmmakers, who

each took up one of the subtitles of the film. ‘The Good’, made by Tamer Ezzat, is about the month of protests in Tahrir

Square leading to Mubarak's resignation. The footage is thrilling, as we see

the seeds of a new culture being sown, where ‘the people’ as an entity, really

do have power. ‘The Bad’, by Ayten Amin,

is about the secret police, several of whom uncharacteristically grant

interviews. This is perhaps the most controversial segment, where the filmmaker

rather than bludgeoning them with the blunt instrument of a crude edit,

delicately allows them to reveal their contradictions and deceitfulness with a

subtlety they perhaps don't deserve, but one that nonetheless shows a confident

and mature filmmaker at work. The final segment, by Amr Salama, is of course about Mubarak himself, and it

lampoons the leader with a piercing wit one might also not anticipate, coming

as it does in the heat of the moment. This film proves that craft needn't be

sacrificed for the sake of politics, even in the midst of revolution.

There

is undoubtedly more to come from this epoch, it feels like more comes each day,

in fact. Perhaps there will be no definitive film from any of these uprisings,

but surely the more we see, the more nuanced a view of the events we'll have.

To that aim, I am curating a program for the Istanbul Film Festival under the

rubric 'Filming Revolution', that will include several contemporary as well as

historical films documenting (or recreating in some cases) revolutionary

movements in the region. I'll write more about that program in my next month's

dispatch.

London Dispatch #48 – January 2012

TURKISH ENglish

Fix Me (Raed Andoni, 2009)

It all boils down to this:

who has the right to a headache… As some of the readers of this column may have

realised, I often write about first person documentaries. I wouldn’t say I’m

obsessed with them, but I’m interested in the tensions between the personal

potential in documentary and the social or political dimensions seemingly

inherent in the form. It can all go terribly wrong, of course, with

self-absorbed people making uninteresting films that have no relevance to

anyone besides their mother. My focus has been, though, on films that manage to

be both personal and political; that succeed in drawing together the particular

and the universal. I have written, for instance, about a first person film

where the filmmaker pursues answers for himself and his family that perished in

the ‘killing fields’ of Cambodia, by ingratiating himself and then becoming

confidant to the second in command of the Khmer Rouge. The film (Enemies of the People by Thet Sambeth

and Rob Lemkin, Cambodia/UK, 2009) is both of significance to the filmmaker

personally, while also in the service of a larger social, political and

historical purpose, eliciting the long withheld truths about a painful and

still damaging period in Cambodian national history. I’ve found myself arguing

both here and elsewhere, that a first person film becomes meaningful

specifically when it brings into relief the relationship between the individual

and the collective, when it speaks not in the first person singular ‘I’, but in

the first person plural ‘we’.

Then along comes Raed

Andoni’s film Fix Me (2009,

Palestine). The premise is simple. The filmmaker goes to a psychologist to try

to unravel the reason for his headaches, which have been plaguing him since

1989. One might expect that he’d go to a doctor, but considering that 1989 was

the year of the first Intifada and the year Andoni was imprisoned by the

Israelis for taking part, one quickly understands that the headaches are very

likely psychosomatic. His mother, in the film, questions him about his

self-absorption, chiding him to be less involved with his own problems. Others

around him, such as the man he shared a prison cell with, cannot understand his

pre-occupation with himself when his people still need him. The film is part of

a struggle for individuation, a claim to one’s right to a headache, along with

the right to one’s dreams and hopes and individual satisfactions. Had it been articulated

by a spoiled American, one might not be so sympathetic, but for a Palestinian

who has given years to the dream of a nation, at the expense of his own

personal aspirations, one is compelled to see it differently. He should,

indeed, have the right to express himself not in the collective ‘we’ of first

person, but really, just as ‘me’, a guy with a headache.

I delighted in this film’s subversion of my earlier

certainties, reminding me that while generalisations may apply, the exceptions

will prove more interesting than the rule. Quite the opposite of naval gazing

self-absorption, I found this film wryly challenging in its demand for a

filmmaker’s right to focus on something so simple, personal and downright

apolitical as his headache. In contrast to my impatience with the indulgent use

of psychoanalysis in Waltz with Bashir

(Ari Folman, Israel, 2008), where Israeli soldiers try to come to grips with

their feelings of guilt at having participated –unwittingly-- in the massacres

of Sabra and Shatila, all the while without taking any real responsibility for

it, I found Fix Me a welcome

antidote, where a filmmaker, rather than hiding behind a collective, is willing

to stand up before it. I had little patience for Folman’s headaches as it were,

but had all the time in the world for Andoni’s. It all depends on who one

believes is entitled to complain, the perpetrator of state violence or its

recipient.

London Dispatch #47 – December 2011

TURKISH ENglish

The Last Rites (Yasmine Kabir, 2008)

How can we characterize an

aesthetics of hell and how can we distinguish it from other forms of

aestheticization? This question came to me while watching the short film The Last Rites (Yasmine Kabir,

Bangladesh, 2008) at a recent 8 day festival of Indian documentary film in

London. It was a 17 minute film

about the infamous ship breaking yards in Chittagong Bangladesh, the subject

several other films that I’ve seen over the past few years. In all of the other

representations of the yard, the filmmakers seem utterly smitten with the

irresistibly photogenic site, the huge hulking tankers, half in, half out of

the water, dwarfing the ragtag army of workers who will dismantle the ships

practically with their bare hands. The breathtakingly beautiful barefoot

Bangladeshis heave steel rope over their naked shoulders singing rhythmic work

songs against the silhouette of the sun, as the mamouth ships stare back

impassively in their statuesque state of decay. This is the visual poetry of

the place, conveyed by the likes of photographer Edward Burtynsky in the film Manufactured Landscapes (Jennifer

Baichwal, Canada, 2006), which can also be described as obscene. Reviewers wax

lyrical: ‘beautiful in its depiction of ugliness,’ ‘a magisterial tour of the

world's most devastating and devastated industrial zones’. The attentive reader

of this column will remember that I excoriorated this film several months back,

precisely for its privileging aesthetics over politics.

More recently I saw

another impressively beautiful film depicting Chittagong and felt similarly. Iron Crows (Bong-Nam Park, South Korea,

2009) delves more deeply into the lives of the workers and gives a better sense

of the working conditions than Manufactured

Landscapes, but it too seems to get lost in the sheer magnitude of the

scale, the broken ships serving as too irresistible a metaphor for late

capitalism, to really focus on the hell of the place. It really is magnificent.

These films and others

sent me into a spin, fretting that aestheticization per se was the problem in

representing, well, hell. Beautification makes such scenes not only attractive,

but somehow inevitable, naturalizing their place on this planet as if they rightfully

belonged and could be justified, precisely on aesthetic grounds. I had begun to

despair, wondering if the cranky anti-aesthetes of the 1970s and 80s really did

have a point, and that if aesthetics were to ever have an oppositional rather

than affirmative politics, they could at best be an aesthetics of garbage—a

term used in Latin America in the 1970s to denote an unadorned depiction of

poverty and destitution, while recycling the detritus of life into art. Yet, in

this new shiny century of surface as depth, images of poverty and recycling end

up being the sign of high art, with films like Wasteland (Lucy Walker, US, 2010) making heroes out of top grossing

artists like Vik Muniz as he dares to dirty his hands working with garbage

recyclers in Brazil. So much for the politics of the aesthetics of garbage.

Luckily, I was able to see Kabir’s short film that

while aesthetically as complex and accomplished as any mentioned above, manages

to convey the visceral truth of Chittagong—it is a hell on earth; a labor camp

no less cruel than Buchenwald or Dachau. With her images, one feels the

impossible weight of the ropes, as shoeless feet are submerged ankle deep in

toxic petroleum; the palpable hunger driving bodies of skin and bone to repeat

arduous physical feats that would make a strong man groan. The film brought me

straight back to Night and Fog (Alain

Resnais, France, 1955) to remind me that aesthetics per se are not the problem,

it is merely the ideological purposes which aesthetics are made to serve that

must be questioned. I am grateful for Kabir’s film for reminding me of this

fact.

London Dispatch #46 – November 2011

TURKISH ENglish

The Green Wave (Ali Samadi Ahadi, 2010)

I

had been hearing about The Green Wave

(Ali Samadi Ahadi, 2010, Germany) since it came out in 2010. Friends had

reported back from IDFA that it was a ‘must see’ film. Combining animation and

interviews with archival material ranging from blogs and tweets to cell phone

video, the film reportedly vividly captured the extreme highs and lows of the

Iranian activist movement from 2009. I have been doing some research on films

of revolutionary movements and this film was high on my list to see. So I

rushed to the Institute for Contemporary Arts in London as soon as the film

opened there.

In

addition to unearthing several interesting films, my research has taught me two

things: The first is that only successful revolutions get to be called by the name

of the country (the French Revolution, the Russian Revolution, the Egyptian

Revolution). Unsuccessful attempts get a colour: the Saffron Revolution (Burma

2007), the Green Revolution (Iran 2009). An exception, though this leads me to

my second point, is the Orange Revolution (Ukraine, 2005). The second thing is

that not everything that is called a revolution should really be considered as

such. This would seem to be true about the movement in Iran, which while having

all of the signature events of a revolution – protests, government crackdowns,

arrests, martyrs, even (and this is a bit old fashioned) a leader — would be

better understood as a corrective to the revolution, not an overthrow. What the

protestors were demanding was fair elections, freedom of speech, and civil

rights for minorities, women, and others, within

the rubric of the 1979 Iranian revolution, not instead of it.

The Green Wave doesn’t explain all this,

perhaps because it tries hard not to alienate its intended audience: young

Western viewers. The film is not particularly informative but is instead an

emotional appeal by a dissident Iranian filmmaker calling on Western viewers to

support the freedom struggles of young Iranians. The film leaves you deeply

moved by a sense of injustice and the bravery of the activists, even if it is

never entirely clear what the actual politics of the movement or the political

platform of its main leader might be. One leaves the theatre with a strong

sense of outrage of the illegitimacy of the Ahmadinejad government, whose

repressive power grab was expressly backed by the Supreme Leader, Ayatollah

Khamenei, but to say the film manipulates viewer’s emotions in favour of the

opposition without indicating its political platform, is simply to state a

fact.

The

film does attest to a brutal period in contemporary Iranian history, one that

is by all accounts still on-going. There is no doubt that power is being abused

and that people are being arrested, tortured, and murdered all because they

dared to speak out in favour of a more democratic future. The film itself was

clearly a labour of love, made in a lightening fast 10 months and juggling

multiple elements, stories, and events, creatively contending with obvious gaps

in coverage. Initially seeded with funding from the Heinrich Böll foundation

and finished with co-production funds from Arte and several other Western

broadcasters, this well-intended film bears the imprints of its intended

audience rather than its subject. The film is scant in substance and heavy in

affect, giving it more pathos than political pull. Still, as a film driven by

passion and commitment, with a strong sense of urgency about it, it certainly

does not fail to leave its intended audience moved.

London Dispatch #45 – October 2011

TURKISH ENglish

Anything Can Happen (Marcel Lozinsky, 1995)

Having just last month

praised a new documentary film festival in London, I’m a bit self conscious now

to be talking about yet another one to crop up in the area. This year

inaugurated not only the Open City documentary film festival in London, but

also the Quadrangle Film Festival, set in

the bucolic English countryside, about 40 minutes outside of London. Some of

the same people were involved in both festivals, which seems remarkable

considering they were held only a few months apart, but the festivals were

quite different at the end of the day. One obvious difference was location.

Whereas the Open City festival did attempt to create a community atmosphere, it

was nonetheless held in a semi-institutional setting on the University College

London (UCL) campus. The setting of the Quadrangle was an 18th

century farm, with a large barn and several outbuildings all retro-fitted for

screenings. Participants camped on the land as if going to a music festival,

but of course, the events were screenings and workshops and the participants

all film enthusiasts and filmmakers rather than your usual festival-revellers.

I was invited there to

give a workshop on first person film and ‘the political’ so I was ‘working.

That didn’t keep me from enjoying the grounds and the atmosphere though. The

sun was miraculously shining, the place was gorgeous, and at least a few of the

films I saw were good. Who wouldn’t love to go to documentary sleep-away camp

for a weekend? Don’t answer that. For me, it seemed like a great idea. This

being the first year, the programming was a bit uneven, with far too many of

the organizers’ friends (local, available, cheap) showing their films. Several

of the films screened were television documentaries (many already screened in

the UK on Channel 4, some still in rough cut form, soon to be broadcast), which

gave the programme too much of an ‘industry’ feel. There was very little in the

way of really inspiring and innovative documentaries, with the exception

perhaps of two ‘lost gems’, the charming Polish doc Anything Can Happen (Marcel Lozinsky, 1995) and a film from the

ever-rewarding Werner Herzog, Bells from

the Deep: Faith and Superstition in Russia (1993). With the exception of

four or five films, every other film screened at the festival this year was

made in the UK, giving the festival an unnecessarily provincial feel. And as

nearly all of the films showcased had already had television screenings, there

was something a bit stale about the selections as well.

I admit, I found this

disappointing, as I had hoped to see films that revealed a much more expansive

idea of documentary as well as of the world. I can only hope that the

programmers realise that they missed an opportunity to bring more innovative

work to their screens and next year I expect to see films from other regions

and other aesthetic inclinations. Another idea for the festival would be to

have it guest curated by people from elsewhere, to bring in fresh ideas and

films that could surprise. I still have faith, despite a slightly flat start,

that this festival will be something to put on my calendar again next year.

Anything Can Happen (Marcel Lozinsky, 1995)

London Dispatch #44 – September 2011

TURKISH ENglish

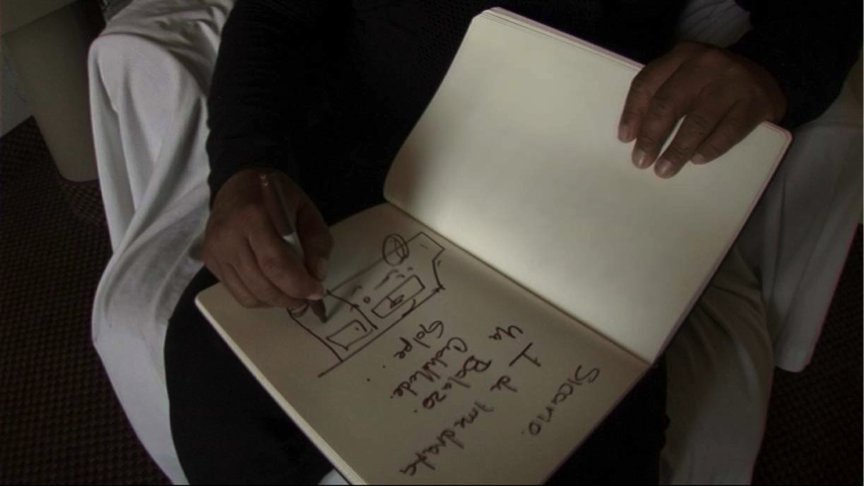

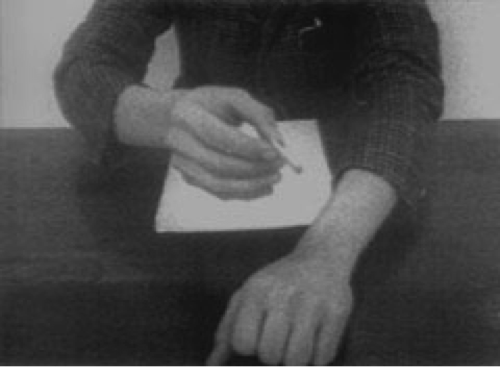

El Sicario: Room 164 (Gianfranco Rosi, 2010)

After a four-year false

start with the London International Documentary Festival (LIDF), a festival

that in my estimation has never really taken off, London has finally gotten a

documentary film festival it can be proud of. The Open City London Documentary

Film Festival, that had its inaugural run in June, seemed to hit all the right

notes with a strong selection of international documentaries, several

interesting strands (such as, ‘Crime and Punishment’, ‘Obsessions’, ‘Field and

Factory’, and ‘Science Fictions’), affordable ticket prices, and a centralised

location at University College London that allowed for an electric festival