blog

“Nothing is poorer than a truth expressed as it was thought.” — Walter Benjamin

The Past as Present: Soylent Green in 2022

"Author's cut" of article published in Film Quarterly Quorum

When a film sets itself in a clearly marked future it risks having the effect of announcing its sell-by date. And yet when you watch said film in the year it has been fictitiously set, two operations inevitably set in: you assess its many failures to imagine what your present day looks like, and then, if the film is any good, you have to concede that where it counts, it got some things dead right. Such is the experience of watching Richard Fleischer’s Soylent Green (1973) in 2022, the year in which the film is set. The uncanny (un)timeliness of the film is profoundly disturbing while at the same time deeply gratifying, as if hearing a voice from the past tell you that your daily anxiety about capitalist induced climate chaos is not only well justified, it has actually been anticipated for some time.

Soylent Green never hit as big as some other sci-fi films of the era like 2001 (Stanley Kubrick, 1968) or Alien (Ridley Scott, 1979) and perhaps for good reason. Despite some A-list actors (Charlton Heston in the lead role of Thorn, an illiterate and corrupt cop with a heart of gold, and Edward G. Robinson in the final role of his career before succumbing to bladder cancer, as his ageing sidekick, Sol Roth), the special effects alone signal more of a B-grade movie. The orange hued ketchup blood and the souped up garbage trucks, outfitted with fearsome long-toothed front hoes amply allude to the tight budget within which they appear to have been working, as does the extremely low-tech futurism portrayed. But nor should this film be dismissed as a flop or even as low-brow ‘trash’.

Soylent Green didn’t become a cult classic for nothing. Along with its B movie aesthetics, it proffers a powerfully resonant dystopian vision of the then future. At the time of its release, it was received with mixed reviews, with critics mostly noting that Charlton Heston’s acting appears to have improved (a fact to which I was insensible), or the powerful effect of watching Edward G. Robinson enact his own death, when in real life he died barely a week after shooting had wrapped. Some critics of the day note the entertainment value of the film and one critic, Penelope Gilliatt of the New Yorker expressed outright exasperation with regard to the passivity of both the women and the poor as depicted by the film (to which I can only heartily agree).

What none of the critics writing in 1973 could have foreseen, however, is the near prophetic view of the absolute callousness of late capitalism wherein profit and the enrichment of the few at the expense of virtually everyone and everything else, reigns supreme. The idea that corporations will stop at nothing to maintain their profits may not have been unknown in 1973, but it surely hadn’t been instantiated as thoroughly as it has since the fall of the other counterbalancing superpower and its anti-capitalist forces.

In the film the main crisis that drives the plot is overpopulation leading to significant food shortages, both issues as real and troubling today as in 1973. At the current tipping point of global warming, the population explosion tends to be a detail overshadowed by the incipient destruction of an habitable atmosphere, and of course many overpopulation arguments are irremediably tainted by racist misconceptions. What remains high on the list of concern is the question of food— namely, how to feed a planet full of people when the climate has become unpredictable and many industrial solutions developed over centuries of imperialist and capitalist exploitation (monocropping, overcoming ‘seasonality’ with complex global supply chains) are responsible for straining the planetary resources even further.

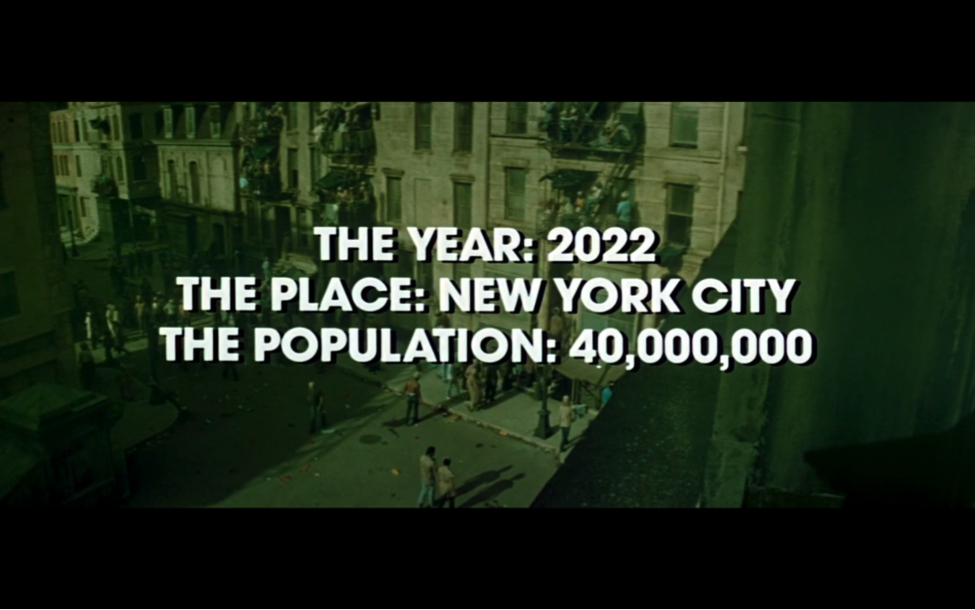

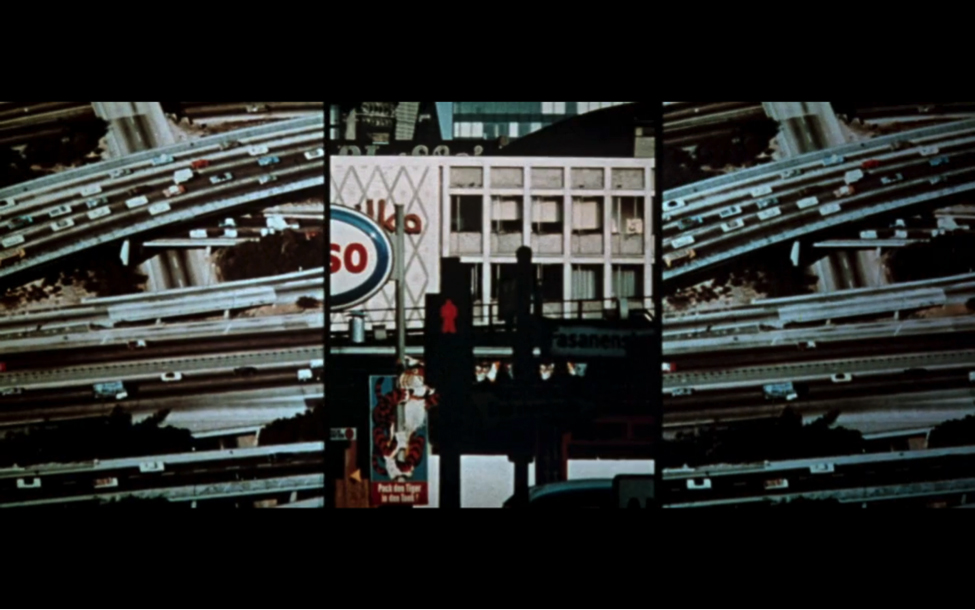

Charles Braverman’s two and a half minute documentary montage that opens the film is a revelation in and of itself and worthy of sustained analysis. Beginning with sepia images of early American settlers, the montage unwittingly apportions blame correctly to the white settler colonists for the maddening pace of industrialisation and the demise of any balanced and respectful relationship with the lived environment. The montage quickly accelerates from its proto-Ken Burns Effect zooms and pulls to a frenzied barrage of cuts and dissolves with some nifty split screen effects that could not have been simple to produce at the time. Comprised exclusively of stills, it manages to convey the dizzying pace of development and its often unnoticed effects. Highways are choked with cars, factory chimneys belch black smoke, people crowd the streets in all reaches of the globe, as mountains of junked cars threaten to overtake the frame and garbage piles up in every corner. The sequence ends with the title of the film, quickly supplanted by the following information: The year: 2022; the place: New York City; the population: 40,000,000. The main problematic of the film is meant to be overpopulation, but the montage tells a more complicated story that includes every indication that climate chaos was already showing its distorted, tortuous, effects. There is even a frame that hints at corporate responsibility with a sliver of Esso’s logo visible, and another frame that tellingly has the word American emblazoned on a massive wrecking ball.

The American Film Institute lists Soylent Green in 77th place for most quoted line of dialogue—some of Heston’s last words which are also nearly the last words of the film: “Soylent Green is people!”. Without going into gruesome detail, suffice it to say that in the film Soylent is the name of the corporation producing food substitutes and “soylent green” is the name of one of their popular varieties of nutrition wafers that were meant to be made with plankton, but with the oceans dying, a more plentiful substitute to feed the world had to be found. In 2014 someone thought so well of this film that they named their meal replacement product ‘soylent,’ presumably in the belief that the film was so obscure that no one would realise the irony.

Indeed, the only people who appear to be returning to this film in 2022 are conservative film critics and film nerds. Wesley Smith, writing for the National Review feels compelled to preface his comments about the film’s prescience with regard to climate change by opining that “if I hadn’t known when the movie was made, I might have mistaken these introductory images for an Al Gore–produced advocacy clip” or “whatever one thinks of anthropogenic climate change” this film gets it right.”1 Tony Sokol writing for Den of Geek, appears to be so dismayed by the current popularity of meat substitutes, that he seems to liken them to the wafers in Soylent Green.2 What those returning to the film in 2022 seem to agree upon is that it hits the nail of climate change right on its proverbial head. In fact, I might add that the focus on climate as the driver of change is more forthrightly posited in this film than in any popular genre film on the topic that I have seen.

The film is no masterpiece to be sure, and there is plenty at which one may take offense (all of the women in the film, with the exception of the head book authority of the “Supreme Exchange”, are literally referred to as “furniture”, and are sold along with the lease in wealthy apartment buildings). They are essentially sex slaves for the rich, and while this is clearly meant to represent a dystopian world, the lives of rich men are portrayed as enviable. Alongside this obviously demeaning trophy sexism comes gratuitous racism: Thorn’s boss, who caves in to the pressures of corrupt senators, is Black.

Still, this film harbours an uncommonly clear message about climate change, overpopulation and over-consumption that is significantly watered down in the more recent ‘cli-fi’ films that have received so much more acclaim. Films like The Day After Tomorrow (Roland Emmerich, 2004) or the more recent Don’t Look Up (Adam McKay, 2021) did better at the box office and certainly the former and to a lesser extent the latter, was received with great fanfare and critical acclaim. TDAT has been credited with changing perceptions (especially in the US) about climate change. (Rust 2012) And yet, the latter two films pale in comparison. Both The Day After Tomorrow and Don’t Look Up fail miserably in the face of scientific fact and indulge in the type of individualism and fatalism that leads exactly nowhere in terms of the collective action required to head-off a global threat of this scale.

Heston’s last words in Soylent Green are not actually “Soylent Green is People” but rather the follow up collective demand: “We must stop them”. This collective call is precisely what is missing from the later attempts to bring popular cinema into the realm of cultural critique. Further, what all three of these films prove, sadly, is the inadequacy of popular commercial cinema to catalyse the necessary response to such a crisis. The effective cultural critique, which Soylent Green had the potential to be, TDAT pretended to be and DLU promised to be, is all too easily subsumed into grist for the entertainment mill, feeding the spectator the activist equivalent of soylent green wafers—"tasteless, odorless, crud”—unable to satisfy anything but the most basic individualist needs and most certainly incapable of nourishing and energizing the bold collective action necessary. Still, there is something to be said for a voice from nearly fifty years in the past speaking directly and viscerally to our deepest fears in the present.

-----

1 Smith, Wesley J. (January 16, 2022). "What 1973's Soylent Green Accurately Predicted about 2022". National Review

2 Sokol, Tony (January 7, 2022). "Soylent Green Predicted 2022, Including Impossible Meat Substitutes". Den of Geek

References

Bass, George (9 January 2022) “In 1973, ‘Soylent Green’ envisioned the world in 2022. It got a lot right” https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2022/01/09/soylent-green-2022-predictions/ Washington Post

Rust, Stephen (2012) “Climate change and Hollywood” in Ecocinema and Climate Change, Rust, S., Monani, S., & Cubitt, S. eds (Taylor and Frances): 191-211

Smith, Wesley J. (January 16, 2022). "What 1973's Soylent Green Accurately Predicted about 2022". National Review

Sokol, Tony (January 7, 2022). "Soylent Green Predicted 2022, Including Impossible Meat Substitutes". Den of Geek

The version of this article published in Film Quarterly Quorum can be viewed here.

Subliminal Blame

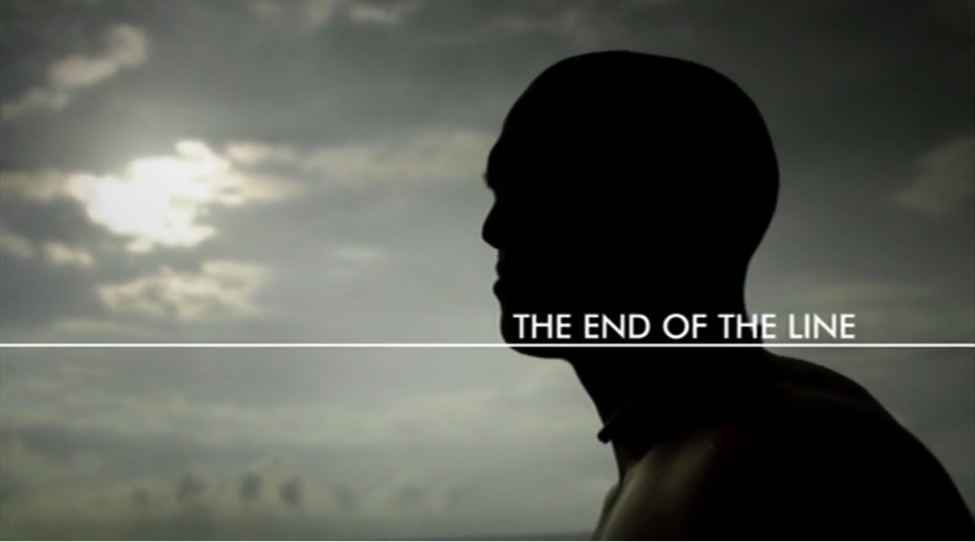

A close reading of the opening sequence of The End of the Line (Rupert Murray, 2009)

Narration begins around two minutes and forty-five seconds in, after a long drawn out credit sequence of the kind normally reserved for fiction features. Ted Danson, probably best known for his role as bartender Sam Malone on Cheers, narrates with a studied earnestness, telling us that the idyllic images of sea-creatures bursting with colour we have just been watching was shot in a man-made underwater refuge in the Bahamas, its rich bio-diversity due only to the fact that it has been protected against “the most efficient predator the oceans have ever known”. Cue the driving Jaws-style musical score and the attendant shots of blood-lusting sharks, as if anyone watching could miss the implication that it is not sharks, nor barracuda, nor even the one-ton-a-day eating Sperm whales that populate those seas that constitute the greatest threat to marine life in this age, but rather it is “man”. After a few seconds of hard driving, rapid fire cuts, we begin to see hints of an industrial fishing vessel, a chain, the side of a ship, with fleeting glimpses of humans mercilessly hunting their prey.

I do a double-take. Then a triple take. Did I just see what I think I saw? Did the filmmakers just code that fiercest, most terrifying, of predators, that enemy of all things beautiful in the sea, as Black? Could they really just have done that, embedding in the viewers’ unconscious, or perhaps simply conveying that which is embedded in their own, the message that while the (over)fishing industry is overwhelmingly the result of both the practices and consumption habits of the Global North, the quick as a flash images we’re shown are, upon second look, unmistakably those of Black men? A hand, a head, a man violently wielding a sharp knife—all Black men.

Granted, the silhouetted head that we see over the film title is generic enough to not be definitively racially coded, but all of the other shots involving men fishing, are without exception, undeniably, of Black men. And the silhouette, with its indistinct palm trees in the far distance, the shaved head and the discernible collar-like necklace all signal at the very least non-western, or possibly even, “primitive” if we want to imagine the worst. But what alternative do we have but to imagine the worst, given that the blame is subliminally and inexplicably laid on those who precisely are NOT responsible for this problem? The only thing that would have had a more absurd ring would have been to replace women of any racial background, or children for that matter, in their place, or perhaps it’s the fish themselves who should be hauling the nets and wielding the knives?

An opening like this reminds me as to why the resistance to the blanket term Anthropocene matters, or at the very least, the necessity of an attunement to the injustices the term reproduces. This brief but all too effective opening of a film that is meant to be about the excesses of a particular industry, but also the excesses of more generalisable so-called human practices, precisely enacts the reasons we cannot be satisfied with any explanation of the effects of the so-called Anthropocene. The Anthropocene is a name of convenience that has come to be accepted as describing the effects of man-made changes that have had a lasting and notable effect on the earth and its atmosphere. And yet, the term would want to rest responsibility for those changes and consequences on all humans equally, throughout the ages. It makes not distinctions between those who have wrought those changes and those who have historically been the victims of those changes. It says nothing about the economic and ideological beliefs that allowed those changes to be enacted and it does not account for the forces and constituencies that should bear the blame and responsibility for our present global condition.

With the term Capitolocene we identify the economic system that subtends this rapacious appetite for growth and profit at the expense of the health of the planet. With Plantationocene we further attend to the systems of human, animal, plant, and planetary exploitation that benefited some and most certainly not others in the process. To generalise about what Donna Haraway calls a “species act” is already doing a great injustice to those many people and cultures who have not initiated nor have they largely benefited from the extractivist exploitation of the planet that is causing our current crisis. It is not the species as a whole who has found it necessary to fritter away the wealth of this planet on excessive indulgences, and indeed, those indulgences have only ever reached the fortunate few, who in real terms are a fractional minority of those humans inhabiting this earth. The rest are literally exempt from these pleasures, though they are often left to live with, in, and among the beneficiaries’ detritus. Just look at the plastic mountains and toxic lakes, rivers and increasingly seas that have made their indelible mark on landscapes throughout what used to be referred to as the “third world.”

If Africa, along with many of the lands colonized by white European colonialists, bears the brunt of the excesses of the appetites of the Global North, it cannot also be made to take the blame for them. And yet, as seen even in this flash-fast, almost imperceptible, opening sequence, that is precisely what the Global North would like to do, even if it does so stealthily and without accountability.

As a documentary film scholar who teaches film studies, I always ask my students to pay close attention to opening sequences. I once, early in my graduate studies, was given an assignment to choose a film and perform a close textual analysis, shot by shot, of its opening sequence. By sheer coincidence, as I believe many of the other films had already been taken, I ended up analysing the opening sequence of the only film ever made collaboratively between two of the so-called “founding fathers” of the English language documentary: Industrial Britain by Robert Flaherty and John Grierson. In what amounted to something like the first 12 or 15 shots of this short film from 1931 I could detect something I hadn’t yet read about in the relationship between the two titans. I was able to discern a tension between the romantic shots of the pre-industrial images and the subsequent shots representing the shift towards industrialisation that the film was meant to celebrate. The close textual analysis allowed me to see something before knowing it, and it turns out to have been absolutely spot on. In that particular film project, which was meant to be produced by Grierson and directed by Flaherty, Flaherty went so far off script in his appreciation of the pre-industrial world of basket and hand-loom weaving and transportation by sailboat, that Grierson ended up firing him and finishing the film himself, trying to salvage something from Flaherty’s beautifully but wrong-headedly composed shots in order to end up with the message that the sponsoring entity, the Empire Marketing Board, would be happy with. The film is a mishmash of mixed messages—Flaherty’s romanticisisation of the pre-industrial age combined with the celebration of the so-called progress that industrialism was meant to bring, that Grierson knew his sponsors would want. All of these tensions are revealed in the film’s very first sequence.

And that lesson, learned all those many years ago when I first embarked upon my studies in film, continues to reward, long after the fashion of textual analysis has given way in film studies to many other tendencies that would appear to be better geared towards making the political economy of film more legible. A recent visit to my sister in Denver had me begging her husband to turn off the lights and come sit down before the film we were watching was to start. His response was that it’s just the opening credits, and that he would come when the film starts. I’m sure he found me pedantic when I said he sounded like one of my laziest students, and that the opening sequence of any film is an encapsulation, in some sense, of the film as a whole. You can learn an incredible amount from these first several shots of any film, and what I learned from the opening shots of End of the Line, is that the filmmakers are, consciously or unconsciously, prepared to place the blame for the avaricious excesses of capital extractivism of our oceans on precisely the wrong culprit. Man is indeed responsible, but which man and for which man’s benefit is the question we must always ask when considering the effects of and responsibility for the Anthropocenic mess we’re in.

The Unintended Archive

Impressions upon seeing Alia Syed’s Points of Departure (2014) and Kamal Aljafari’s Recollection (2015) on one long Spring day in London

Still from Recollection (Kamal Aljafari, 2015)

Two films in one day, two archive dives yielding nothing but absence, yet yielding, in both cases and completely coincidentally, to the filmmakers’ will to be seen in the unseen. The archive is never a full load, it never fully returns the embrace, never adequately enlivens at the touch of a curious hand. It coyly withholds while holding out the promise of full satisfaction. There is only so much it will present, especially to unexpected suitors. When Alia Syed, a Pakistani-Scottish-British filmmaker, is offered a chance to make any film she wants drawing from the BBC Scotland archive, it is the archive that is surprised, not the artist. The artist knows she’s unlikely to find herself or her likeness amongst the thousands of hours of footage. She searches, dutifully, but will not find. The archive, however, is simply unprepared. It never imagined this moment, never had any image of her in its head. There are films aplenty, and even some about South Asian immigrants to Scotland, but they were never meant for her to see. They were meant for the people, the eternal hosts, the owners of the image. Who, it turns out, always had a very limited imagination, that did not figure on her active presence. She looks, she sees, she is profoundly unmoved. She nonetheless, in an indirect move of resistance, a deflection of sorts, decides to use other images, images of destabilization, slum clearances, homelessness, as well as images of weaving, spinning, cloth making, a trade that has no connection to her past save for a beloved lace tablecloth that she could not throw away as she clears her father’s house, a cloth bought and borne of Scotland, yet so much a part of her father’s house that she could not bear to part with it. So weaving and cloth, wending and wharfing, incessant machinations of industrial lace-making: the fullest extent to which the archive can be shaped to her needs. It gives in but without bending. By the end of this battle of wills, one intentional, the other institutional, in the last moments of the film, this filmmaker forces the archive to offer up the signs of its repressed images; she finds a little mixed race boy at the edge of a frame. A single shot of half a boy, a ghost who haunts the entire archive, insistent yet semi-obscured. He can only be a weak stand-in for all that the archive misses and misrepresents, meekly hovering at the edge of the frame, tentatively yet stubbornly announcing his presence, and this demi-world vision is enough to undermine the entire promise of the archive.

Kamal Aljafari takes an altogether different approach to the archive in his film Recollection. Aljafari also mines the archive, though not one that has been purposely or publically collected. His archive is a wealth of fiction films made by Israeli directors, shot in his hometown of Jaffa. It turns out Jaffa was a favorite setting for Israeli films, so there’s no shortage of imagery. Jaffa provided the perfect backdrop to Israeli drama, giving them the aura of an historical presence in the land they had only recently settled. For the Israelis the problem was getting rid of traces of Arab life, still vibrant if muted in the city. For Aljafari, the problem was to recoup the traces that could never be fully erased and which press insistently at the corners and margins of the frame. He spots his aunt’s house, the local café, a family friend’s car. He scours these images in search of home, the very home the Israelis have tried with their fictions, as well as with their ideology, laws, and wrecking balls, so hard to destroy.

Like most fiction films, these Israeli films foreground their characters, yet the bodies of those actors interfered with Aljafari’s view. It’s as if he had to figure out a way to crane his vision to see past the action, around and behind the main event, as it were. He does this by digitally removing those in the path of his forensic sight. Using fairly basic technological tools—AfterEffects, mostly—Aljafari deftly disappears the Israelis, leaving mostly buildings and roads but also the occasional Palestinian, spotted from afar on a balcony, or in a doorway.

Against all odds, he even finds his uncle in one scene, looking literally lost, as he wanders haplessly across the frame. One wonders how his presence was justified within the film’s narrative, as (not unlike Syed’s little boy) he lurks eerily in view. With the Israeli’s disappeared, Aljafari reclaims the spaces of his childhood and young adulthood, his memories veritably reconstituted amidst the wreckage. He stages a cinematic return to a territory otherwise occupied, a reconnaissance tour of that which was never supposed to be seen.

In perhaps the most deft reversal ever effected in cinema, the digital intervention that up until now has been understood as the biggest threat to documentary authenticity, suddenly becomes its greatest ally, transforming otherwise fiction films into the indexical referent of documented Palestinian existence. Despite all odds, it allows Aljafari to exclaim “we are here!”, thus revealing the fiction of Israeli ‘history’ in that land and affirming the documentary truth that Israelis have gone to such lengths to deny.

The films were not screened together nor did I set out to see them both on that one single day. But the double viewing prompted me to consider the effects of the unintended archive, when the archive itself is subjected to treatment for which it had never been intended and the results transform the promise it holds out: exposing historical omissions, reversing wilful erasures and in the process, transforming historical fictions into stubborn and ineradicable fact.

Note: For a brilliant review of Recollection that makes a similar yet distinct argument, see Adania Shibli’s 8 April 2017 review in Ibraaz.

A Tale of Two Films

What the Fields Remember (Subasri Krishnan, 2015)

Last

week I watched two films, one on Thursday, the second on Friday. On Thursday I

went to see Spectre, as all

self-respecting queer feminist film scholars who specialise in documentary

must. For reasons that continue to elude me, Bond seems to be one of the only

exceptions, not just for me but for many I know, to a general disdain for

testosterone-fuelled, generally racist, sexist and homophobic action films. Why

does Bond get a pass when virtually none others do, I really can’t say. Perhaps

it has something to do with the tinge of camp that lingers around the edges of

his too immaculate, too suave, too impossibly genteel persona. And perhaps too

because Bond, unlike some other action heroes, seems to be changing (ever so glacially,

but changing nonetheless) with the times. By now he’s only about a decade or

two behind the times, no longer the Neanderthal he once was with regard to

gender and sexual relations at least.

Be

that as it may, I saw the latest Bond film, and enjoyed it more or less, with

the sense that perhaps the formula was wearing slightly thin, but more

importantly, that I might be getting a tad too old to weather the bursts of

adrenaline and vexed attention required in the viewing. I was already exhausted

after the nail biting, vertiginously shot, helicopter scene, staged beautifully

over the Zócalo in Mexico City. I wanted to check my phone to see how much more

of it I’d have to survive, but I didn’t dare disturb my neighbors who seemed to

watch with wrapped attention (and a handy flask of whiskey in their grip).

Besides, I knew we couldn’t be more than 10 minutes in.

Spectre (Sam Mendes, 2015)

The

next night found me in virtually the opposite environment, swapping plush,

reclining, stadium seats for rigid chairs with built-in desks, and a 30’ screen

with sensurround for a dim data projector and two studio speakers. The film I

went to see, in a SOAS classroom, was an understated, meditative documentary

about the barely remembered “Nellie Massacres” that occurred in Assam, India,

roughly 30 years ago, a xenophobic mob killing spree lasting only 6 hours, that

ended with up to 10,000 dead. What the

Fields Remember (Subasri Krishnan, 2015) was having its third small screening in

London, having just been completed this Autumn. There are no serious prospects

for distribution deals outside of India and no expectation of major audiences,

let alone direct political effect.

I

don’t honestly think two films could be more different. Where one is pervasive,

saturating screens globally, the other will barely ever get seen. Where one

wears its multi-million dollar budget on its screen, the other is clearly made

on a shoe-string. Where one cuts long before you’ve even fully registered the

shot, the other lingers as if painstakingly extracting information, with the

patience of a prospector from the mute earth.

The

film reminded me of some of the more thoughtful documentaries I’ve seen, films

like Susana de Sousa Dias’ film 48 (2009),

which privileges affect over content in its treatment of the audio interviews

of political prisoners in Portugal, counter-intuitively yet effectively making

their testimonies that much more powerful, or Rithy Panh’s S-21: The Khmer Rouge Killing Machine (2003), where survivor and

jailers are framed together yet never levelled into an equivalency, due

precisely to the heightened sensibility of the filmmaker in relation to the

subject. It also harkened me back to some of the more aggressive,

perpetrator-led films of late (The Act of

Killing immediately comes to mind), if only because it so clearly eschews any

such sensationalist strategies, despite the fact that there are similarities to

be drawn, most notably that the killers have never been called to account and

remain not only at large, but in power.

What the Fields Remember is a film that knows how

to listen, to observe, that insistently yet respectfully seeks to draw out its

subject, without compromising dignity or playing on emotions. Choosing her

characters carefully and never privileging words over images for too long,

Krishnan subtly suggests that there are many ways tell a story, and the most

interesting are not necessarily conveyed linearly through narrative. The

filmmaker was present at the small screening, and was so refreshingly

thoughtful and articulate about her new work, that I could have listened to her

forever.

I

found it intriguing that a film about so gruesome a topic could soothe my soul,

after the assault of the previous night’s action-packed adventure film with the

inevitably happy ending. What that says about me, perhaps is better left aside

for the moment. Granted, What the Fields

Remember is not only grim in its recollection of history, but in its

resonances in the anti-Muslim sentiments of contemporary India, and yet, what I

found reassuring was its approach. Intelligent filmmaking, with a sensibility

that privileges subtle undertones rather than garish overtones, that is

politically insightful, attentive to detail and the particularities of the

event and the context, while always striving to be formally inventive, this is

what I long for, and this (not the subject matter, I can safely say) is what

relieved my harried sensibilities from the night before. I much prefer to be

jarred by history than by flashy stunts, explosions, and special effects, it

turns out. Good to know.

Keywords:

Spectre, James Bond, Political Documentary, Subasri Krishnan, What the Fields Remember, Susana de

Sousa Dias, 48, Rithy Panh, S-21: The Khmer Rouge Killing Machine, Act of Killing

A Syrian Love Story for his mates back in Hull

Footage openly criticizing Assad, from A Syrian Love Story (Sean McAllister, 2015)

Trigger

Warning: this is a rant. I had not meant for my first blog post to reveal my

more lacerating tendencies, but there you go. The screening of a much-lauded

film in England about Syria that I felt compelled, or rather practically propelled,

to see, prompted this admittedly provocative response. And for the record, I am

about as fond of trigger warnings, as I am of the film about to be discussed.

Two

things tempered my experience of watching A

Syrian Love Story (Sean McAllister, 2015), both related to the filmmaker’s

presence at the Bertha DocHouse screening I attended in London. The first was

by way of introduction. The filmmaker wanted to thank his producer for all the

work she had done on the project, having forgotten to do so in the initial

screening of the film at the cinema that week. He self deprecatingly

acknowledged that he was so busy pandering to the members of the audience

affiliated with the BBC and the BFI that he simply forgot to mention her. He

then introduced her solely by first name and described her as more his

secretary than his producer. Following this inauspicious beginning, he proudly

announced that he would have bought her flowers, but he’s from Hull and “boys

from Hull” don’t buy women flowers. Not only had he endlessly gendered her

contribution in typically derogatory ways (is this really how one treats one’s

producer and if so, what does that say about the filmmaker himself?) but he further

managed to denigrate it as if really all she had done was make his appointments

and his coffee.

The

second inauspicious remark was made in the Q+A after the film, where the

filmmaker insisted proudly that no matter where he makes his films, Japan,

Yemen, Syria, his primary audience is always the same: his mates back in Hull who

don’t travel the world like he does. This may not sound like a damning

indictment to all readers, but it smacks of precisely the islander

provincialism that would allow for a film to be made about one of the most

complex and intractable political and humanitarian crises unfolding today, in a

way that very nearly bypasses those complexities in favour of a familiar

generic mould that could console an ignorant viewer in Hull. Transform the

tragedy of a failed revolution turned bloody civil war, into a personal tragedy

of love, worn thin by the inchoate tensions of an indecipherable external world

pressing in on an otherwise “normal” [read: “just like us”] household. The

assumption is that the politics of the situation are beyond the grasp of the

simple publicans of McAllister’s hometown, but that love and difficult

relationships are something we can all understand.

Further,

we learn early in the film that McAllister is a filmmaker in search of a

subject and when he finds a suitably dramatic scenario (loving husband bringing

up a family while wife is unjustly imprisoned by a despotic regime) he recklessly

homes in on their personal lives, probing their inner emotions, soliciting

responses to leading questions, captures incriminating footage (of the family openly

criticising the Assad regime, for instance), endangering their lives to the

point of forcing their flight from the country, and then in effect,

contributing to the ruination of a delicate yet viable relationship. The style

of interviewing consists of, in essence, dogging the family members in English,

a language most can barely speak, to simply repeat (mimic) the words he

provides them with in the first place, thus confirming his place as voice-giver

to these otherwise inarticulate subjects. He plays therapist to a family in

crisis, with none of the training nor the emotional maturity to do so. A boy

from Hull, who can’t even bring himself to respect his own producer properly,

grants himself the powerful position of peace-maker and arbiter of a family drama

that so far exceeds the limits of his emotional intelligence as to be an act of

aggression in and of itself.

Here

we have the worst of the filmmaker-adventurer, who blithely and with all of the

entitlement of a (former) imperialist culture, takes and exacerbates a family

crisis all for the exalted goal of enlightening his ignorant friends back home.

The worst part about it is that everyone, from his commissioning editor at

Channel four, to the powerful decision makers on BBC1 who made the unprecedented

decision to broadcast it there, not to mention the 4 stars given it by Mark

Kermode in the Guardian, are contributing to the filmmaker’s own

self-congratulatory belief that his film is indeed a great masterpiece fusing

art (tragic love story, a la Romeo and Juliette) with geo-politics in a way the

great and good, if somewhat naïve and unworldly, people of England can

understand.

The

problem isn’t with the great people of England per se, who may or may not need

to pandering to such a degree, but with the condescension of the filmmakers and

commissioning editors, who would prefer to distil a complicated and intractable

situation down to a story of star-crossed lovers, doomed by external

circumstances beyond their control. Was it even external circumstances beyond

their control that forced the family to flee Syria in one night, with only a

flimsy suitcase and no proper papers? Well, in a sense, yes. If McAllister hadn’t gotten caught with the

footage of the family still in his camera, they might have been able to stay in

their home and had time to come to grips with their situation. Yet, given the

risks this family had already undertaken as vocal critics of the regime even

before the uprising and ensuing war, it is inconceivable to me that a filmmaker

could add to the danger they already faced. Made that much further unimaginable

by the fact that his continued filming was evidence of his implacable pursuit

of his story—the unfolding drama, in part catalysed by his negligence and

misplaced priorities—had to find its conclusion. Tragic or happy, it had to be

resolved one way or the other and he would track them down wherever they might

be (Lebanon, France, Turkey) I order to get the footage that would complete his

story. More than once the subjects of the film question him as to why he is

still there, filming them.

I

have devoted my life to the documentary. I have made films and have studied

others’ films. I write about, think about, and watch documentary during more of

my waking hours than I can account for. Yet sometimes, when faced with films

like this one, I hate the form. Documentary, thankfully, is so much more than

this type of ambulance-chasing story-telling factory, needing human fodder to

churn out gripping content in order to fill meaningless (if self-important) television

programming hours. It can and often does do justice to the intricacies of

history, to poetry, to life in general. It is the filmic form best suited for

critique, defamiliarization, intellectual and ideological transformation. But

when documentary goes for ratings, it generally does play to the simplistic

formulas that palliate the fear of the other, transforming it into an anodyne

reflection of ourselves—a reassuring message that no matter how different

people may seem, we’re all the same in the end. Whether we are or are not all

the same in the end, our circumstances are wildly different, as is our mode of

expression. Imagine if Amer and Raghda, the couple at the heart of the film,

could have expressed themselves in their native tongue, how much less naïve and

basic they would have seemed. Yet that complexity had to be disallowed, in

order for McAllister to tell a simple tale.

This

is not an indictment of documentary per se. It is an indictment of the career

documentarist who doggedly pursues people as if they are merely material for a

story he can then, in effect, tell back at his local, over a pint. If you

intend to point your camera at people, be sure that it is their lives, more

than your career or your mates back home, that you are concerned with.

Moreover, it strikes me that if there is any responsibility associated with the

documentary filmmaker, it is precisely not to reduce their subjects to objects—mere

matter for their message. There are so many ways to resist the formulaic and

the simplistic, yet if opportunism is driving the filmmaker forward, as in this

case, they are unlikely to make the effort to see what is actually there,

preferring instead to shape the material into well-worn, familiar patterns.

Keywords: Documentary film, Documentary ethics, Sean McAllister, A

Syrian Love Story